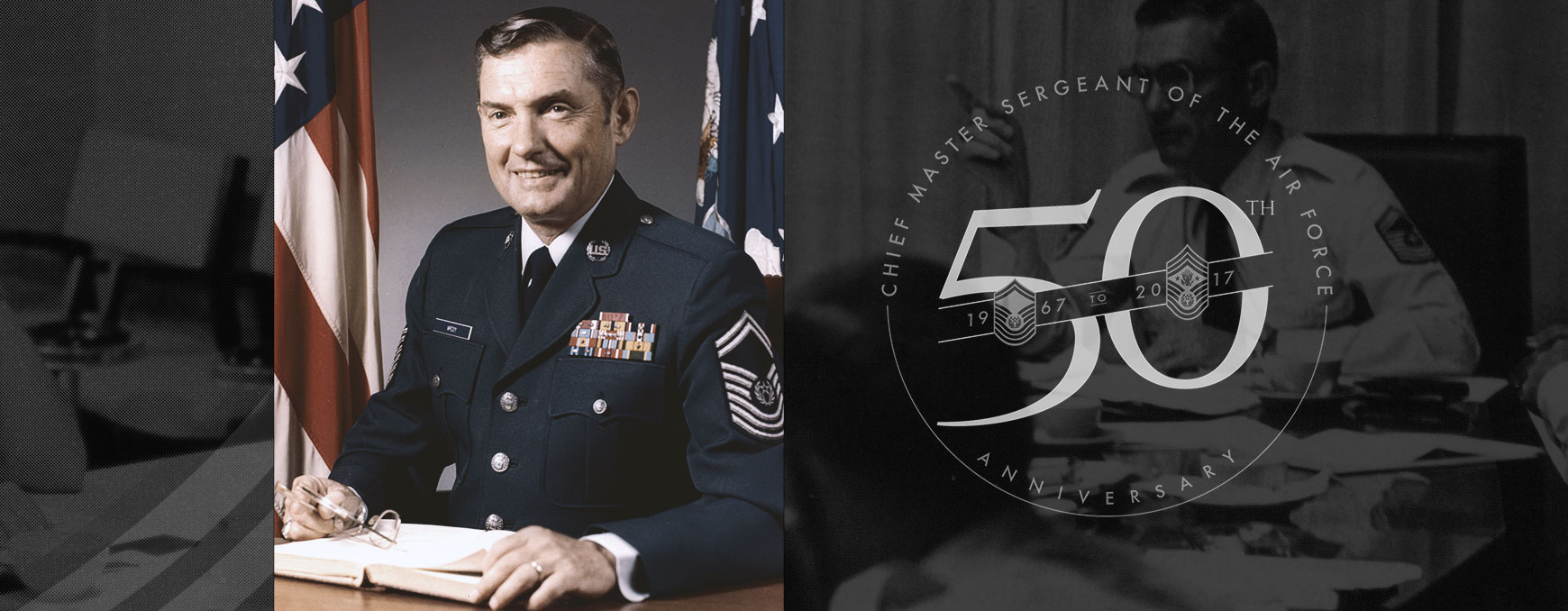

CMSAF James M. McCoy

James McCoy was sure he would become a priest. He was born in Creston, Iowa, on 30 July 1930 and attended a Catholic prep school and St. Benedict’s College. But after a period of reflection and prayer, he decided against it, choosing instead to join the Air Force in January 1951.

McCoy became a radar operator and quickly moved through the ranks, rising from corporal to technical sergeant in just five years. He then became a military training instructor and followed the path of education throughout his career. After a two-year tour in the Philippines, McCoy became a Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) cadet instructor, then a noncommissioned officer (NCO) preparatory school instructor, and later the noncommissioned officer in charge (NCOIC) of professional military education (PME) for Strategic Air Command. In 1974 he was selected as one of the USAF’s 12 Outstanding Airmen of the Year.

In July 1979, Gen Lew Allen Jr. selected McCoy to be the 6th Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force (CMSAF). McCoy quickly set out to improve the enlisted retention rate, which had dropped to as low as 25 percent in the late 1970s. He implemented the Stripes for Exceptional Performers Program, improved discipline, and expanded PME. He retired in November 1981 but continues to stay in touch with the Air Force. He speaks to every class at the Senior NCO Academy, and his namesake’s Airman Leadership School at Offutt AFB, Nebraska.

McCoy sat down for an interview in September 2015 to reflect on his life before, during, and after the Air Force. During the interview McCoy spoke about his passion for PME, how close he was to becoming an officer, and his excitement after being named Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force. The following are edited excerpts from the conversation.

Well Chief, we often learn about our former chiefs in the PDG [Professional Development Guide], and one of the first things it says in the PDG about you is that at one point you considered going into the priesthood, but you changed your mind and ended up coming into the Air Force.1 I’m curious as to why you changed your mind and how you ended up in the Air Force?

Well, first of all, let me go back to the priest business. I did have a vocation. I spent four years in Maur Hill High School, which is a prep school for St. Benedict’s College, St. Benedict’s Abbey, and I was convinced that I had a calling, but I got a year in at St. Benedict’s, and I said, no, that’s not for me.2 So I went home. Of course, my mother was very upset, because she was convinced that I should have been a priest. And I said to myself, well, that’s not my calling. Instead, I joined the Air Force.

I joined the Air Force because I almost got drafted into the Army, and I didn’t want to do that. I had already gone to a recruiting office. I had already talked to recruiters and, actually, basically signed some papers. I was a junior at St. Ambrose College in Davenport, [Iowa,] and my dad, to this day I do not know how he got a hold of me, late 1950, and he says, “Son, if you’re still thinking about joining the Air Force, you better do it today because your draft notice is on the dining room table.” In those days, if you got your draft notice, if you actually received it, you were drafted. So I got on a bus and went down to the recruiting office, signed the papers, and the rest is history. But I did have a calling, and I’m very proud of that calling. And I think that, you know, who knows where I would have been if I’d finished that calling. I wouldn’t have been Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force, that’s for sure.

Maybe this was your calling in the end. You joined, I think it was late 1940s, early 1950s?

January of ‘51.

At the time the Korean War had begun. And, we often talk about World War II...and you hear about Americans coming together to support that war. Then you hear about Vietnam, and how many Americans were against that war. What was the feeling amongst Americans, and the public support for military members, at the time you joined?

Well in 1951, actually 1950, when I got the notice from my dad, the American public was very sincere about young men serving in our country. And I say young men because at that time not too many women were serving the country. So I felt it was my duty to do that. I felt like I needed to be ready in case, because I knew I had a low draft number, and I knew I was going to get drafted. But anyway, the consensus of the American people in the early ’50s was, serve your country and do it well.

One of the things that is interesting about when you joined is that we were still a very young service. What do you remember about those early days? I think at one point you were a corporal before we even had the Airman ranks. Did it feel like a separate service at the time?

Well, I think the best way to answer that was that we were so young, and we were trying to figure out what the Air Force was going to become. I remember I went through Lackland [AFB, Texas]. I remember the men and women, or the men that went through Sampson [AFB, New York] were issued the olive drab uniform, but they got one stripe. They were a PFC [private first class]. So I started as a private. I was then a PFC, and then I was a corporal. On our wedding invitation, it says Cpl. James M. McCoy. On 1 April of 1952, I woke up one morning and I’m no longer a corporal. I’m an Airman second class. And we had Airman third class, Airman second class, and Airman first class. One of the things I remember distinctly is when I wanted to get married, I had to get permission because I was only an E-3, a corporal. So I had to get permission from my squadron commander to get married.

Did the stripes change at that point too?

No. We had the regular, we had the new stripes. We had the one stripe, the two stripes, and the three stripes. And so we had all those up until [CMSAF #10 Gary] Pfingston was chief when they changed the chief stripe.

You said you had to get permission to get married, which is interesting—well, first, how did you meet Kathy?

Actually, it was kind of interesting. My sister introduced us, and it was at a college bonfire in St. Ambrose College in Davenport, Iowa. Nancy, my sister, says, “I want you to meet somebody.” So she introduced me to this young, lovely young lady by the name of Kathleen Loretta O’Connor. I said, “Boy, she has to be a good Catholic with a name like that.” And she was and still is. But that’s how we met. She could probably tell you more about it, but...

How did she feel when she became an Air Force spouse?

Well, I left her on the back porch of her house in Dixwell Court in Davenport, Iowa, crying because she didn’t want to see me go. And I was probably crying too. And her dad was mad at me for a couple of years because I left his little girl and went off to war. But when I came back, I had gained about 30, 40 pounds. I was pretty big. That was that good chow hall food. Anyway, so we kicked it off from there. And we got married, and I got trimmed down a little bit. So it was a great experience for both of us.

You were promoted fairly fast. In 1956 you were a technical sergeant, and you were selected to become an MTI [military training instructor].

Well, first of all, the reason I got promoted early was because in those days we had frozen career fields. If you were in certain career fields, you couldn’t get promoted. I was in a career field that was brand new—instructing training career field. So I went up pretty fast. And as a result of going up pretty fast, they said since you’re an instructor, you need to come down to basic training and help us with basic training. So I became an MTI. I wasn’t pleased with that, but it was a great experience. Being a tech sergeant, I didn’t have to push troops, but I had to supervise about 15 young Airmen to do it.

I had in the meantime attended OCS [officer candidate school]. I got five months into the course, and I was eliminated. Five of us were eliminated from the course, and it was because of the scoring system that they had. Not too many people know that, and so it’s kind of an interesting thing, what if? What if I had become an officer? I wouldn’t be sitting here as the sixth Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force. Who knows what I could have been.

Was that a disappointment for you then?

It was a big disappointment. I almost left the service. Not only was I eliminated from OCS, I was shipped to the Philippines by myself, leaving Kathy back in Davenport, Iowa. So I was extremely disappointed. And I was taking it out on myself. But a good friend of mine, a master sergeant, World War II veteran, got me under his wings and said, “McCoy, you got too much to offer. Get yourself straightened out.” And to this day I thank him for that because I did. I mean, I eventually got her to come over, and we spent a year over there. We had another child in the Philippines, and so it was quite an experience.

What did that teach you? Did you learn about the meaning of service at that point? You know, it’s a lot of sacrifice.

Well, the services today have changed so much as to when I came in. In those days, you’re pretty much on your own. And I can remember the first sergeant I did have in my organization, he says, “Are you a member of the NCO Club?” and I said, “No.” And he says, “Well, you should be. Come on down.” So we went to the club. Guess what? He got plastered out of his mind on my money, and I had to go home to face her with all our money gone. So a little bit different in those days. But I think I learned a lot in those early years of my military life: how important it is to take care of your people. And that was my emphasis even when I became Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force because I wanted to make sure our people were well taken care of. Get involved. Get involved in everything that you can possibly do.

We created the senior and chief ranks around that time. You were a technical sergeant, and at that time master sergeant was the highest you could go. What do you remember about that change?

Well, we were in the Philippines at the time, and I thought to myself, “Well, I got one more stripe to go.” Seven, or eight, nine, 10 years of service. And after the change I thought, “Wow. Now I got another two more stripes to make.” But, again, going back to that first sergeant/master sergeant, he told me, “Don’t give up. You got too much to lose.” So I did. I studied. I finished my college degree and continued on to do the best I could. After the Philippines, we went to the University of Notre Dame. I went on AFROTC [Air Force Reserve Officer Training Corps] duty there, and that was a great experience. I wish I could have spent more than one year. But, again, manpower cuts cut my slot, so I have a history in my first 10, 12 years of getting my slots cut. And so I had to go and ended up down the highway to a Strategic Air Command [SAC] base called Bunker Hill AFB in Indiana. What a change that was.

Yeah, I imagine. You spent quite a bit of your career, actually, in the training environment.

I did.

What drew you into that path?

Well, I guess one of the things, as I think back on it, was my experience on ROTC duty leading the cadets. You know, they were going to be our future officers, and I was bound and determined that they knew the difference between officer and enlisted, and that they had the emphasis on enlisted in their portfolio. So I think that was a challenge for me.

When I went down to Bunker Hill in the early days of the Airman Leadership School, they called it prep school in those days. In the first prep school class I stepped into, it was Noncommissioned Officer Preparatory School. They were staff sergeants, but 12, 13, 14 years of service, again, because of the frozen career fields. I said to myself, “Something’s wrong here. Just the picture is not right.” So, I made a little promise to myself if I ever get up to a position where I can do it, I want to change that.

Well, actually, I did. I got to SAC Headquarters, and we named it the NCO Leadership School. Now it’s the Airman Leadership School. So through the years, I’ve seen the evolution of that.

Now if I understand it right, one of your students was [CMSAF #5 Bob] Gaylor; is that correct?

Yes, it was.

What do you remember about teaching him?

I taught him everything he knows except the 3 Bs, as I say sometimes: “Be brief, be bright, and be gone.” He never has learned that one. He still hasn’t. But anyway, Bob was in the class I taught, and I taught human relations and management.

I remember one day sitting in class, this was at Barksdale AFB in Louisiana. It was pretty warm outside, and the air conditioning had broken. It was right after lunch. He was sitting in the corner I think, and I was going through this lesson plan as best I could, and I could see I was losing the class. I was talking about performance standards, and performance standards had certain subjects you had to weigh. So I went through the process of what you do to get the weights—and I looked at him and I said, “Sergeant Gaylor, what do you weigh?” He woke up and said, “165.” So I thought that was the end of the class.

But the other thing I remember about the NCO Academy. I was at the NCO Academy when President Kennedy was shot. I was in class and I was teaching emotions, and you talk about a touchy subject to get through.

So later, we shut down the school, shut down the Academy. Everybody went different ways. I went to the base at Barksdale. Bob had to go to Utapao in Thailand. And while he was over there, I was working in personnel at Second Air Force, and I had the opportunity to see the chief promotion list. Well, guess whose name was on there? Bob Gaylor. So I went to the clothing sales store, got a set of chief stripes, and went out to see Selma [Gaylor] and their four children, and I told them that Bob had got promoted.

So Kenny [Gaylor, Bob’s son,] said, “We need to celebrate.” So we did. And Selma says, “I think there’s a beer in the refrigerator.” So he went over and got it. And to make a long story short, which I have a tendency not to do, I went over and drank his beer. That was his coming home beer.

Oh, no.

He had told Selma to leave it...don’t let anybody touch that. So he returned home from Thailand, and he tells Kenny, “Bring me my beer, my coming home beer.” And Kenny says, “Jim McCoy already drank it.” So that’s how far we go back.

Thank you for sharing that story. I think one of the things you talked about is how PME is different today. One thing that is quite different is that each command had its own school. Each school was similar, but different. And of course today all the PME schoolhouses operate under the Barnes Center. Do you think that has been a good evolution?

Oh, yeah. First, I was the SAC senior enlisted advisor at the time, and I had control of the three academies in the command. Well, it actually came down to one academy by then. We could pretty well pick and choose what we wanted to teach. But the change was the right thing to do; it was the right move. We had some academies and some places around the country that were teaching small arms—how to carry arms. And other ones were just concentrating strictly on speech. So, we didn’t have a standardized curriculum. We developed our own curriculum. So by establishing a college for enlisted PME, which is now the Barnes Center, we standardized the curriculum, and we’re doing the right thing.

I have some trouble with them every now and then because they want to go a little bit too far than I think we should be going, but it’s still standardized. And what we’ve done is we’ve been able to develop our academies and our leadership school, but more importantly, the great young Airmen that we have today.

Thinking about how it was back then and looking ahead to how you would want to develop Airmen, would you say we hit that mark?

We did. It was the right thing to do. When I became the chief, I knew that the best thing we could do was to expand that and get it better, even make it better.

There was a lot of heartache because we took away the funding that the commands had put into the academies and leadership school. Some commands like SAC, they put a lot of money into it, and they wanted to make sure they had the right curriculum and the right facilities, and so forth. And so some of the commands were a little bit put out with that, because now they had to put it in their own budget process.

In 1967, when Chief [Paul] Airey became the first Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force, obviously that was a significant moment in our history. We look back at it now and think of it as a major change. Was it just as significant then, when you heard the news that we had made that move?

Well, yeah, that was—and you probably know the history of this. If Gen J. P. McConnell hadn’t appointed Chief Airey as the first one, we wouldn’t have this. We would have had to rely upon Congress to do it, because there was an emphasis within the Congress, Cong. L. Mendel Rivers [D–SC] had started it. You know, “Air Force, if you don’t do that, I’ll pass a law requiring you to do that.” Well, the leadership of the Air Force at that time got the message, and that’s when Paul was selected.

And Paul would tell you today if he was here, God rest his soul, that the first six months he was in the job were the hardest six months he had ever spent in his entire career—and he was a POW [prisoner of war] in World War II—because he had to sell the position. A big push, and he had to sell it to Gen. McConnell. And after about six months, Gen. McConnell called him in and said, “You’re right, Chief. I made a mistake. This is what we need.” He thought it was going to be somebody who would be in the chain of command and would do all these things, but it wasn’t. And we never were that chain of command. We were there to advise the leadership of the Air Force.

So, you know, it was a positive mood. I was stationed at SAC headquarters at the time, and I remember when Chief Airey made his first visit to Offutt and came in on an airplane. I said, “Whoa. Got his own airplane.” I thought that’s a pretty cool job. So people said, “You ought to be thinking about that.” And I said, “Okay, I’ll think about it.” I never thought it would happen.

And yet it did. One of the first things Chief Airey did was develop a new promotion system (WAPS), and you had made chief right before that was implemented. Was that a necessary change at the time?

Well yeah, again, going back to the frozen career fields, we had a lot of people that couldn’t get promoted unless somebody died or left the service. So, it was the right thing for the Air Force to do.

I know when it first came out there was a lot of controversy about it because you had to test, and you had different points for this; different points for that. We had to educate the force on why we did this. And as a result of the change, we had an equal opportunity promotion system. The frozen career fields went away; we didn’t have them anymore. We had people retiring at 20-years’ service as a staff sergeant because they couldn’t get promoted. And here I was just rapidly going up the ranks—and I wasn’t the only one. There are a lot of other career fields like that.

How long did it take, I guess, to normalize across the force?

The WAPS system?

Yeah.

Let’s say probably three or four promotions cycles. People had to get used to it. And a lot of the old timers that were against it eventually retired, so I would say three, or four, or five years. It was pretty well accepted when I became Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force, and that was 1979.

One of the things I found interesting when I was reading about you and your career was that you considered retiring early. Then you changed your mind, and you went on a different course. Can you talk about that moment?

I love to talk about that because this young lady over here [Mrs. McCoy] had a big influence on that decision. What had happened was we were at SAC headquarters. I had 19.5 years of service. I had made chief when I had 16 years in the service. An assignment came down, and we had a large family. We have eight children. I called Kathy, and I said, “We got to talk about this.” In those days, if you had an assignment, you had seven days to accept the assignment or retire, and I was eligible for retirement as I could have retired at 20 years.

So we really discussed it quite a bit, and I said, “We need to talk to our children.” One of the things we always did was sit down together for dinner. Well, we called them around, and I said, “We’ve got some news. We’ve got a new assignment.” And they asked, “Where are we going?” “We’re going to Hawaii.”

Well, the little ones were jumping up and down. They were happy. Debbie left the room. Her mother went in and found her laying on her bed crying and sobbing, “I do not want to go. I don’t want to go. Please.”

How old was she at that time?

She was a junior in high school.

I see.

So, that was a big decision we had to make. It was tough. It was tough with Debbie. I think as we both look back on it, Kathy and I, not only did Debbie go to Radford High School, she won the biggest scholarship that you could win, and went to Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. And she was watching some guy by the name of Paxton playing lacrosse. He was an All-American lacrosse player, and he was a couple of years ahead of her. So to make a long story short, they ended up getting married. And I think she’s done pretty good because he’s now the assistant commandant of the Marine Corps.

I promised Debbie the day she married him that I’d say something nice about the Corps every day. So, I said it today. Period. Check it off.

Done.

That was a big decision it really was. We went to Hawaii, and we got caught up in a four-year assignment. Thanks to the Air Force Association, I was selected, I should say we were selected, as one of 12 Outstanding Airmen of the Year.

We came to Washington, [DC,] and we met a general by the name of Gen Russell E. Dougherty, and he asked us questions in the receiving line. We were still stationed in Hawaii. And he said—he particularly asked Kathy, he said, “Is Jim serious about coming back to SAC?” And she said, “Yes, he wants to come back to SAC.”

So later on that evening, he came back over to us and said, “Well, think I know a few people in Strategic Air Command. We might get you a good assignment to Kincheloe [AFB, Michigan], K. I. Sawyer [AFB, Michigan], Minot [AFB, North Dakota], Grand Forks [AFB, North Dakota]—all those great northern-tier bases.” Unbeknownst to me, he was interviewing me to be the first senior enlisted advisor.

Was that, basically, establishing the position?

Exactly.

And how did that work?

Well, SAC was the last command to do it, but I had a lot of good mentors that were in the other commands help me establish the position at SAC. Plus, I had a great group of chiefs right there in SAC headquarters.

When Gen. [John C.] Myer was the commander of Strategic Air Command, he had 12 chiefs. Kind of like the 12 Outstanding Airmen, he had 12 chief master sergeants. He would take two or three of them on the trip with him, and each time a different one.

And they probably got together one time, when Gen. Dougherty became the commander, and said, “What do we need to do?” He says, “Do we keep this program, or should we go to one?” And they unanimously said, “Go to one. Go to one.” And fortunately, I was the one.

You were one of the students in the first Senior NCO Academy class. What was the curriculum like in that first class?

Well, biggest thing I remember about it is was when we reported in. We were stationed in Hawaii, so I came in with my golf clubs, and people said, “What have you got there?” I looked at the curriculum, and there was a lot of time on our own there, so a couple of us did that.

But to try to answer your question, the biggest challenge was we were there to figure out what we should teach and when we needed to teach it, because the Academy was still being built. It was a program that needed to be done, and needed to be developed for senior NCOs. We kind of took that upon ourselves.

It has changed quite a bit. One of the things you do, almost every class, is go down there to talk to the students. So you’ve seen it develop into what it is today.

Oh, yeah. It’s kind of interesting to look at the class today and compare it to what it was 20 years ago when we started bringing the former Chief Master Sergeants of the Air Force in. We still had trouble with weight. We still had trouble with hair. We still had trouble with how to wear your uniform. The force now today is what I envisioned it would be when I was Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force. And so, I think we’ve come a long way in that respect, and we’ve done a great deal for—not only for individuals like yourself, but for those young Airmen coming behind you.

We’ll skip forward to when you became the sixth Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force. Can you describe the selection process? How did that work for you?

Well, each command could nominate. Some commands depending on the size, SAC for example, could nominate three people to meet a board in San Antonio [, Texas]. I was one of the three out of SAC. It was different than it is today, because today the commands only nominate one person. There were 27 or 28 of us that met the board.

It was a general officer, and Chief Gaylor was on the board as the present Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force. There were several colonels, and he was the only enlisted person. Colonels and one general officer. So, it was quite an experience.

Well, they pared it down to three of four of us. Four of us had to go up to the Pentagon and meet with the DP [deputy chief of staff for personnel], which is the A-1 now, the vice chief of staff of the Air Force, and the chief of staff of the Air Force. We did not meet with the secretary of the Air Force. Today it’s a little bit different.

So, you know, at that time Gen. Lew Allen was the Chief of Staff of the Air Force. So we had interviewed with him, and, again, I was the SAC senior enlisted advisor, and so I was anxious to find out what was going to go on.

Later I was back at SAC Headquarters, and Gen. Allen called Gen. [Richard H.] Ellis. The exec answered the phone, and he knew it was something about me. That’s all he knew, because Gen. Ellis was very quiet, very closed. He closed his doors all the time.

So he got on what we called squawk boxes in those days, and says, “Come up. I need to talk to you.” Well, I knew something was going on and the selection had been made. So I walked up the stairs to Gen. Ellis’s office and I thought to myself, you know, “What if?” And the other side, “What if I don’t?” I had close to 28, 29 years of service, and that would pretty well make up my mind.

So I walked up there and walked in his office, and Col. Murphy was the chief of staff, and he was kind of a grouchy old guy, you know. He looked me and said, “What do you want?” I said, “Gen. Ellis just called me.” He said, “He called you?” “Yes, he did, Colonel, he called me. He wants to see me now.”

Gen. Ellis was sitting behind his desk, and he wore Ben Franklin glasses like that. He was reading something, and as he looked up, he took off his glasses and had a great big smile on his face. Gen. Ellis hardly ever smiled. He was just one of those World War II–type generals and had a great career. He said, “Congratulations.” And I thought, “Holy crap.” He said, “You’re going to be number six.”

This is a Friday morning, and I said, “Can I tell anybody?” He said, “No. You’ve got to wait ’til the message flows.” So I said, “Can I tell my wife?” He said, “Oh, yeah.” Well, I was on my way out the door, and his aide was sitting there. He knew what was going on, he was a young captain. Well, in those days SAC had a looking glass. You know, airborne command post. So by the time I got home that night, Friday night, everybody in the Strategic Air Command knew I was going to be number six. So, it was quite an experience.

When you became the Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force, it was an interesting time in our history. It was after Vietnam, and we had begun to draw down. A lot of people referred to it as the hollow force. Why did they use that term?

Because first of all, retention was down and recruiting was down. The force was hollow, and we didn’t have enough people on the list to get into basic training. When Gen. Allen called me in, he says, “Chief, I want you to concentrate on two things. Make sure the recruiters are doing their job, and secondly, make sure the MTIs, are doing their job. We got to get the right people in. We got to get the right people trained.” So that was my chore for two years. And it was tough thing to do because our recruiters were just banging, just trying every which way to get anybody in. And some of the people they brought in were just dirtbags, if I can use a term that, God rest his soul, [CMSAF #9] Jim Binnicker used to use. So, we really had to concentrate on watching that they went through basic and tech school. It was a difficult time.

Fortunately, we served during a period of time when we had a change of administration, from the Carter administration to the Reagan administration. We got to go to President [Ronald] Reagan’s inauguration. It was on the west lawn of the Capitol, and it was the day the Iranian hostages were released. And you talk about euphoria in our country that came out of that. So, yeah, from then it was just, it was a great, great time, because Congress was back with us. The American people were back with us. I say us: the military.

Sure.

So, I know I talked to my counterparts in the other services, and they went through the same thing. The Master Chief Petty Officer of the Navy came to the office one day, and he said, “Jim, I don’t even have enough senior petty officers to put our ships to sea down at Portsmith [Virginia].” So it was a tough time. It really was. Retention was horrible, and morale was even worse. But with that change of leadership in the government, it all changed.

Was it instant?

Well, I wouldn’t say it was instant, but it was very noticeable that it was the right thing for the country to do. I would say from where I sat, it was getting to be very noticeable. In about the summer of ’81, right after the election, the five senior enlisted of the services went to sit down with Sen. Jim Exon [D–NE] who was the senior senator from Nebraska. He talked to us and said, “The reason I called you over here is because I want to hear from you guys. I was an NCO during World War II. Why are people leaving the service?” Well, Bill Connelly [sixth Sergeant Major of the Army] pulled out a pay chart and laid it in front of Senator Exon. He said, “You ever looked at pay chart, Senator?” And the Senator said, “No, why?” And Bill said, “Well, look how many pay raises are over 20 years of service to 22 and 26. So he said, “Well, we’ll fix that.” Well, it didn’t get fixed until [CMSAF] Pfingston’s time, because it just got caught up in conference committees and so forth. But that had a lot to do with retention—they knew it was going to come because we emphasized it.

One of the other things you focused on was expanding your role. When Airey took the position it was new. Each chief afterward formalized the position a bit more, and you were trying to expand it. Can you explain why you were focused on that?

Well, again, it goes back to our focus on retention, to make sure we got the right people in the right jobs. During those times I think one of the things we did was with the senior NCOs. Master, seniors, and chiefs could wear their rank up on the shoulders of their uniform shirt. It was approved during our watch, and it stayed until Chief [CMSAF #14 Gerald] Murray was the chief. He called me one time, and he said, “We’re going to do away with it.” I said, “I’m surprised it lasted this long.” But it was a retention thing. And it was trying to get the senior NCOs a little bit more status, a little bit more recognition. And it worked. I think it worked.

Paul Airey just ate my backside up one side and down the other. Several times he told me, “When I die and go to heaven, I don’t want St. Peter to think I’m an officer.” I said, “Paul, don’t worry about that.”

He was upset, and he never did accept that, God rest his soul. But Paul Airey was one of my great mentors. I’ll never forget the day that I became the chief. I walked back to my office after the ceremony, with the US emblem on, and he called me. He said, “I got one piece of advice for you, Jim.” I said, “What’s that?” He said, “Stay humble. Stay humble. Don’t let it get to your head.” And I hope I did that. I still hope I can be humble like that.

The position today, I think you would agree, continues to expand a little bit. It’s the same, but different. Did you ever think that the role would become what it is today?

Well, really when I was in it I was hoping that in the future I’d see the emphasis that’s being placed on it today. First of all, you’ve got to keep in mind that a lot of our senior leadership in the Air Force, the officers never had a senior enlisted advisor. They didn’t know what it was. So, those of us that were young at the time had to develop the position, and I’ve seen the progression.

For example, I think I only testified twice in two years before a congressional hearing. Now, Chief [CMSAF #17 James] Cody and the rest of the senior enlisted leaders, they’re over there all the time. So, yeah, I’ve seen a lot of changes from the fellas following me and up to the present day. And, you know, a positive change. The big thing that I respect about it is that the following chiefs have kept us involved. We go to senior academy. We’re allowed to do that. We’re the only service that does that. The other services do not. They don’t take advantage of their former senior enlisted leaders.

What do you think that does for us? I think it’s an important thing you just mentioned. It’s rare. Why is that valuable?

Well, I think the fact that when a new program is developed in the Air Force, we’re usually the first ones to learn about it. And, you know, we can voice our opinion. It’s tough on the present.

Yeah.

So, I think it’s a plus for the Air Force that they keep the senior enlisted leaders around. I don’t know why the other services don’t do that.

We really celebrate our former Chief Master Sergeants of the Air Force. You mentioned coming to the Senior NCO Academy, we read about them in our PDG. Every Airman knows who the past Chief Master Sergeants of the Air Force are, which I think is another important point. It ties us to our history.

Right.

A couple more questions before I let you go. Let’s talk about advice for chiefs. You mentioned Chief Airey talked to you in the first few days, saying be humble. The chiefs that are leading today in our Air Force, what advice do you have for them?

Well, during my career—particularly when I was in SAC—I saw people that were supposed to be in a leadership position, the senior enlisted advisors in the bomb wing, or tanker wing...all they did was drive their wing commander around. I said, “That’s not your job. Your job is to inform the wing commander. Your job is to tell him what he doesn’t want to hear.” That was my big point, tell it like it is. That’s a key to a lot of our leadership today, and that’s what we emphasize to young senior NCOs.

Almost 35 years after you retired, you’re still very involved in the Air Force. You have a great perspective both of young Airmen and our senior NCOs. If you look at our Airmen today, and you had to start a sentence with “I believe,” what would you say?

I believe what we’re doing is the right thing to be doing. There were a lot of things during my career, after my career, and so forth, that, you know, I was not in favor of. But by the same token, I got on board. I had to quit living in the past. And I tell people that because I hear a lot of people that have no idea. They say, “Well the Air Force isn’t like it used to be.” Well, it’s not supposed to be like it used to be. It’s not supposed to be like when we were serving. Because they’re better.

I look at the education level of our enlisted force today when I go to the senior academy. It’s amazing. We’ve got people with PhDs—enlisted people with PhDs, master’s degrees. When I retired in 1981, I was one of the few chief master sergeants that had a bachelor’s degree. And that’s because I came in the service with two-and-a-half years of college. I almost got drafted. But I finished, you know, tuition assistance and so forth. So, you know, I believe that we’ve got to keep moving forward.