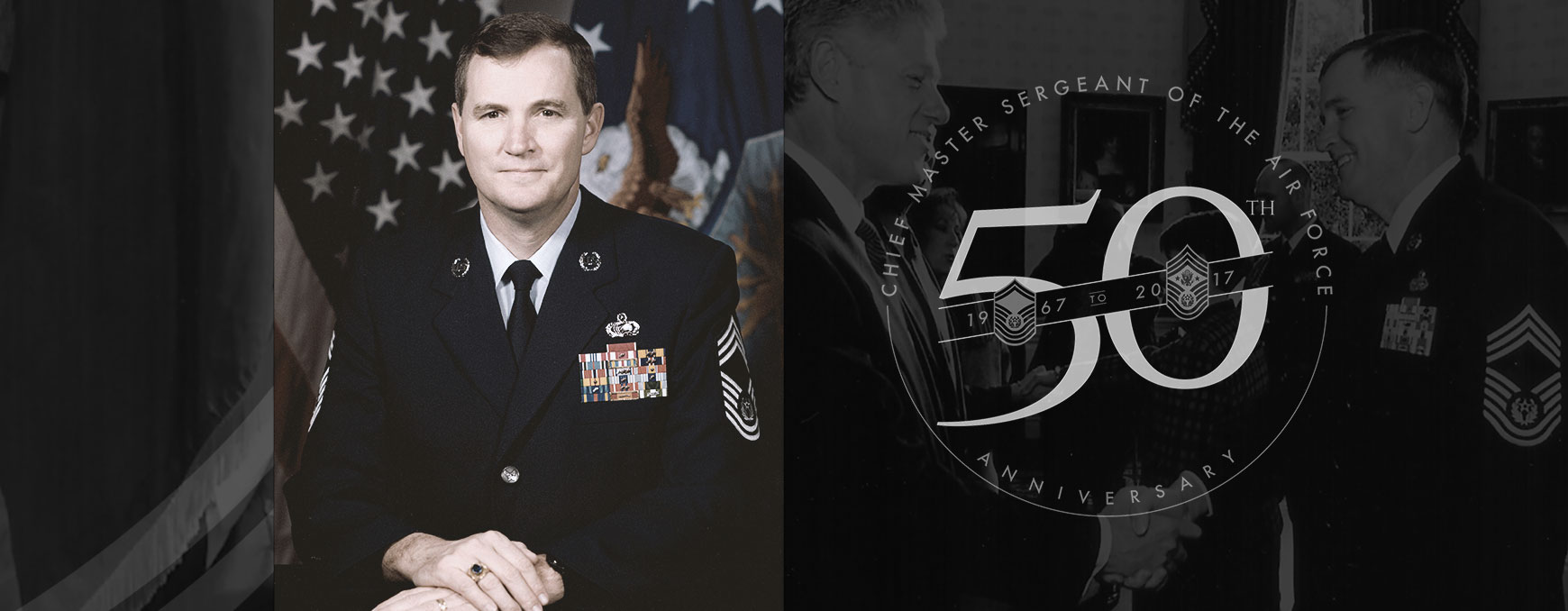

CMSAF Eric W. Benken

At the age of 18, Eric W. Benken felt quite literally out of options. He was born on 20 August 1951 and grew up in Norwood, Ohio, just north of Cincinnati. After high school, he moved to Houston, Texas, with his family, but he found it difficult to find a steady job. In 1969 most employers refrained from hiring the young men who were likely to be drafted into the Army at age 19. After working in low-paying jobs for nearly a year, he decided to pursue a different option and enlisted in the US Air Force.

As a young Airman, Benken transferred to Taiwan and deployed to Vietnam. He experienced the lack of standards during the draft era, and learned about the importance of leadership and the critical role of the first sergeant. He served in Texas, Florida, Arizona, and Korea during his early career, and later served in Belgium at the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s (NATO) Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE) headquarters and in Germany as the US Air Force in Europe (USAFE) senior enlisted advisor during the midnineties, when the Air Force was heavily involved in peacekeeping missions following the fall of the Berlin Wall and the breakup of the Soviet Union.

Gen Ronald R. Fogleman selected Benken to serve as the 12th Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force (CMSAF) in November 1996. During his tenure, Benken focused on the continued transition to an expeditionary air force, the professional development of the enlisted force, and the need to strengthen the culture and spirit of Airmen. Following a number of mishaps, he and General Fogleman, along with Secretary of the Air Force Sheila Widnall, announced the Air Force Core Values and introduced the Little Blue Book, a move that solidified core values and moved the force further along its path toward the professional force of today.

Benken sat down for an interview in August 2015 to reflect on his career in the Air Force. During the interview, he spoke about his first supervisor, a female Airman, and how that shaped his perspective on women in the service. He also spoke about the mishaps that drove Air Force leadership to introduce the Core Values, and the impetus behind changing the title of senior enlisted advisor to command chief master sergeant. The following are edited excerpts from the conversation.

Alright Chief, you voluntarily joined the Air Force during the Vietnam War. At that time the military wasn’t necessarily popular; so, what made you decide to enlist?

It was 1970. I graduated from Norwood High School [Norwood, Ohio] in 1969. Prior to my graduation, my family had moved to Houston, Texas, where my parents were going to start a business; so, I lived with my grandmother while I finished school. After graduation, I felt obligated to join my family in Houston—besides, I really didn’t have anywhere else to go. I found it very difficult to get a job because I would be draft eligible when I turned 19. Employers did not want to hire someone, spend money training them, only to have the Army take them away. There was no college money—as a matter of fact, going to college was never discussed in my family. Norwood, Ohio, was an industrial-based city, and it was expected that you would replace your father on an assembly line at a factory. So, I wound up working in a car dealership. I was washing cars, delivering cars; and with a lot of overtime, I was probably making about $40 or $50 a week.

One day my mother picked me up from work in my old ’62 Chevy. It was a very hot day in Houston, and I had been sweltering in front of an incinerator all day burning trash. As we were making our way through downtown Houston, we became stuck in a traffic jam. I looked out the car window at the federal building. There was a recruiting poster that said, “Join the Air Force!” I told my mother, “I think I found a way out of Houston, Texas.” I said, “I’ll take the bus home.” I got out of the car and walked in, went up to the recruiter, and said, “I want to get out of Houston, Texas.” He said, “I can make that happen.” About three months later, I was on my way to Lackland AFB [Texas] and became an Airman basic.

What did your mom think? Was she supportive of the decision?

Oh, yeah. Back then your mom and dad felt they had an obligation to care and be responsible for you until you were 18 years old. After that, it was, “Okay, you can leave the nest now; it’s time to go.” She was very thrilled for me. I came from a very patriotic, blue-collar family. As I previously alluded to, my dad was a factory worker. My parents strongly supported the troops and the Vietnam War. I was kind of far right when it came to politics, especially when it came to the war and supporting our troops; so, my parents saw joining the Air Force as a natural fit for me. To this day, I have zero regard for hippie war protestors, pacifists, and draft dodgers. To me, they take everything this nation has to offer and give nothing in return. And again, it was a way to get me out of the house and away from the dinner table.

Good. So, you went through basic training, head to your first duty station, and one of your first supervisors was a female Airman. In today’s Air Force that is, of course, normal, but back then it was a little bit different. What did you learn from that experience?

Well, it was kind of ironic. Remember, I joined the Air Force to get out of Houston, Texas. Following basic training, I was placed in casual control, awaiting orders. Finally, they arrive, and my first assignment was Ellington AFB [Texas]. I asked a buddy of mine where Ellington might be, and he said, “Houston, Texas.” I couldn’t believe it—I was about to be stationed 25 miles from my front door. There were hundreds of bases all over the world, and I get one from Houston. My Air Force specialty code [AFSC] would be 702X0–administrative specialist. I was very happy to be in administration. My dad had made me take a typing course while in high school—against my druthers—and it would help me immensely in getting started in my new career.

Anyway, I showed up at Ellington AFB as a direct duty assignee, without benefit of going to technical school. I was very naïve, saluting and reporting to everyone in uniform. I was chewed out by the cop at the gate for saluting him and told to report to the orderly room and sign in. There was no sponsorship program, no family support center, etc. You were on your own. I showed up at the orderly room and reported in to SSgt Rudy Medellin. Again, I was informed that enlisted Airmen do not salute other enlisted Airmen and that formally reporting in was not a requirement. Rudy began typing away on a manual typewriter. He prepared my chow hall meal card pass and my liberty pass, which allowed me to go no more than 50 miles from the base without being on official leave. When he finished, he said, “Look behind me. Do you see that guy back there?” All I could see was a thick hairy arm and cigarette smoke rolling up. I said, “Yes, sir.” SSgt Medellin said, “Well, let me tell you something. That’s the first sergeant. You never want to see him. You never want to see your first sergeant. If you do, it’s because you screwed up. You did something wrong. You didn’t read the detail roster; you missed an appointment. You never want to see the first sergeant.”

I was at Ellington AFB for nine months before I went overseas, and I never saw the first sergeant. I never forgot that encounter or that advice, and it would forever influence my expectations for first sergeants in the future.

SSgt Medellin also told me, “Your supervisor is MSgt Elizabeth Quiatkowski. I responded with, “Did you say Elizabeth?” “Yep, her name is Elizabeth.”

You have to realize that at that time in our Air Force, women were kind of a rare commodity. They represented a very small percentage of Airmen serving. When I went through basic training, they referred to sister flights, but we rarely saw female trainees and only when they were marching. So, to hear that my first supervisor was going to be a female was a bit of a shock. I was a little apprehensive and took a lot of kidding from my fellow Airmen in the barracks. As it turned out, she was absolutely one of the best supervisors and mentors anyone could ever have. We were still a draft force and bringing in a lot of people who didn’t want to serve. They hated the Vietnam War; they were anarchists and dope addicts. MSgt Quiatkowski took me under her wing and made sure I didn’t hang around with the wrong people. I was an impressionable 18-year-old, and she knew it. She insisted that I maintain my standards—the same standards I had learned in basic training. She told me when I needed a haircut, corrected any uniform deviations, and monitored my time at the Airman’s Club. She would allocate my time around the base, making sure I received on-the-job training that coincided with my career development course book work. She gave me feedback at the end of every single day. She was tough as nails. She could curse like a sailor if she wanted to, but it was all in the context of getting her point across. One day, I heard a commotion and looked through the crack of the door to the commander’s office. She was standing in front of his desk. All of a sudden, she leaned over and was pounding the desk with her fist. She was letting him know exactly how she felt about something, and her passion was very obvious. I just assumed it had to do with taking care of the troops—because that’s what she did.

Before I left for overseas, she completed my Airman Performance Report [APR]. Her final comment on the report said something to the effect—“The Air Force might consider retaining Airman Benken.” Looking back I suppose she was marginally in my corner when it came to retention. Anyway, she was an awesome supervisor, and she set me on the path for any success I would have in the future. She lives in San Antonio, Texas.

Oh wow, fantastic.

Absolutely, I called her a year or so after I retired on a whim and told her who I was. She said she kind of remembered me, but she really didn’t. She said, “Well next time I go over to Wilford Hall, I’ll look at all the pictures of the former CMSAFs. Then I’ll know who you are.”

As the role of women expanded in our Air Force, did that experience give you a positive outlook?

Absolutely. Of course, I always appreciated the strength of women—my mother had a lot to do with that. She was a very strong person. My mother left school in the ninth grade. She had lost her father when she was only six or seven years old, and she began supporting my grandmother and her younger sister when she was very young. She worked continuously while we were growing up and overcame her lack of education in a variety of roles and jobs. She left no doubt in my mind—before I ever joined the service—that women could do anything men could do. So, that was kind of a given, but Elizabeth certainly reinforced that idea.

When I entered the Air Force in 1970, women served in a small number of career fields—typically administration, personnel, supply, medical, etc. We did not have integrated training. As a matter of fact, when men went to the rifle range, women went to a class to learn how to properly wear makeup. They did not get the opportunity to fire the weapon. They were referred as “WAFs,” representative of the “Women’s Air Force.” If there were enough women on a base to warrant it, they had their own WAF Squadron with a WAF Squadron commander. So in essence, they reported to two commanders—their operational squadron commander, and for administrative purposes, to the WAF Squadron commander. It wasn’t until 1973, I believe, that women were accepted into nontraditional roles and became vehicle mechanics, aircraft maintainers, etc. Basic training was becoming gender integrated. And rightfully so—as more and more women came into the Air Force, it became intuitively obvious to Air Force leadership they could do anything a man could do and there should be no glass ceiling. We broadened the aperture of what they could do—to the point where very quickly they could serve in 99 percent of all of our career fields. The only exceptions would be in special operations—combat control, pararescue, and joint terminal attack.

In 1995 there was an incident at Aberdeen Army Proving Ground where several trainees were raped by a training instructor, and it precipitated an attempt by some in Congress to overhaul our training methodology. They fundamentally wanted us to return to the separation of genders at basic training—in other words, train women and men at separate locations on the base. It was a return to preintegration days and absolutely the wrong thing to do for our Air Force.

Some congressmen who had never served in the military made this their quest. There were two commissions formed, with the expectation that the services would stop gender integrated training. When they didn’t get what they wanted with the first commission, they formed another to get what they wanted. There was a lot of pressure on them from civilian female activists and the Christian Coalition, who, in my mind, just felt that women should not be serving in the military at all. They very much objected to women fulfilling any kind of combat role. Of course, this was at a time when the Air Force was opening security forces and other combat-related career paths to women, along with them flying combat aircraft.

My boss, Gen Mike Ryan, told me this was my issue to fight and that he fully supported me. I had multiple conversations with House and Senate members—one of them resulting in an exchange of four letter words in the basement of the Pentagon. I wrote several editorial rebuttals and an op-ed piece that appeared in the Washington Times. I was accused by one member of the House of “lobbying Congress,” which is against the law. Our Air Force legislative liaison office rebutted the charge, saying I was “passionate about the issue, and the Air Force fully supported my position.”

I wrote an especially terse letter to a senator (who never served) that was so edgy General Ryan told me to send it from my office without clearing it through the legislative liaison. I recall him wincing as he read the content. I very much appreciated his support. The senator did write me back, and obviously did not agree with my position—to put it mildly.

In the end, my service counterparts prevailed, and our services were allowed to continue training within our respective services as we saw fit. They were going to set women back in our military, and that was absolutely wrong. We fought that very hard.

I’m very proud to be able to look at the evolution of women in the military and how they serve today. We take the way we train and how women serve in our military for granted—it certainly wasn’t always that way.

That’s good perspective. Shortly after you arrived at your first assignment, you went to Taiwan and then Vietnam. In the past you’ve mentioned that wasn’t the best experience. Can you expand on why?

I left Ellington AFB and went PCS [permanent change of station] to Ching Chuan Kang (CCK) AB, Taiwan, for a 15-month tour. I would be assigned to the 314th Tactical Airlift Wing. It was a C-130 outfit supporting the airlift requirements and missions in Vietnam, which was still a very active place. By now I was 19 years old. My departure date was New Year’s Eve of 1970.

My port call would take me through McChord AFB, Washington. I recall standing around in the lobby of the air terminal, waiting for my flight. The glass door to the flight line opened up, and several US Army Soldiers entered and came toward me. They were still in their jungle fatigues and combat boots. I remember them rushing past me heading toward the latrine. Several minutes went by, and they came out—wearing civilian clothes. Later, I went into the latrine and noticed they had stuffed all of their uniforms into a trash can.

Our service members were not welcomed home the way they are today—it was a very sad moment for me and one I could not fully comprehend at the time. It was a sad commentary on our society. Decades later, our nation would attempt to rectify the way our service members were treated during that time.

When I arrived at CCK, I once again reported to the orderly room, where I would be issued my two sheets, my blanket, and a pillow (without a pillow case). I never met the commander or the first sergeant.

Somebody told me I was going to be in Quonset hut number 217. It was January and very cold, with a strong northerly wind. When I arrived at my new living quarters, I noticed the actuator to the door was broken and it was swinging wildly. The cold wind was blowing through the hut. I also noticed there was no order to the open-bay arrangement. Airmen had pulled their bunks and lockers into semicircles, partitioning themselves off in some sort of attempt at privacy. Then a little further down the Quonset hut, you had another situation like that.

There wasn’t any discipline like we had in basic training. I couldn’t figure out where I was supposed to go. Fortunately, somebody said, “There’s an empty bunk over here. So you can come into this circle.” It was very obvious to me that nobody was checking on us—there were no inspections and no adult supervision. During my entire tenure, no senior leader came to our living quarters, and I quickly found out why. Keep in mind, I’m 19 years old, and I’m dealing with people that never should have been in the military. They were drafted. They were unhappy. We had terrible race relations at the time. It was a carryover from all of the social machinations we were going through during the ’60s: all of the drugs, sex, rock and roll, and all that. The racial attitudes and elements were infused into that as well. There were fights—constant fights. The smell of marijuana would permeate the hut. There were awful things happening, and I couldn’t understand why no one would fix it. Again, I would go my entire tour and never meet my first sergeant or commander.

In August, I deployed to Tan Son Nhut AB, South Vietnam. Again, I never met my first sergeant or commander. We lived in a two-story, wooden hooch with sand bags and concrete barriers. We had a bunk, locker, and mosquito net. I was assigned to Det 1 834 Air Division and worked for the deputy commander for maintenance. My brief tenure there had me guarding weapons on a flatbed truck while they were transferred to an Army location. I had been in-country for a couple of days and was placed on a detail guarding weapons with no training and no earthly idea what I would do if the truck was attacked during the ride to the off-base location. A 19-year-old with a loaded M-16 and no orientation or training—a recipe for disaster. But I survived. I found the environment to be even worse than Taiwan. Drug use was prolific, with a lot of it being exported on C-130s back to Taiwan and other countries in the theatre.

So prolific that Chiang Kai-shek, who was the premier of Taiwan, basically said, “Okay I’ve had enough of this!” He fenced off our flight line and posted his own guards at the entry points. This was the environment we were in, and it was kind of like being in a prison. It became so bad that Col Andrew P. Iosue (who eventually became a four-star) was sent there purposefully to become our wing commander and clean it up. He found people that had a militant attitude, both black and white, put them on airplanes, and sent them back to the States.

So, you can imagine, when people say to me, “We need to bring the draft back.” I’m going, “You’ve got to be kidding me.” I never want to see the day when we have draftees in our military. Everyone should be a volunteer. That is why we are the most respected and feared military on the planet—because people want to be there and want to serve. No more hippies and derelicts.

How did that experience shape your career and your leadership perspective?

Well, it certainly shaped my perspective of the first sergeant and what they should be. But to put things into perspective, remember that first sergeants at the time were dealing with a lot of bad people. Their primary job was to administratively discharge the screwups. They typically had five or six people in the queue to receive an Article 15 or a discharge. That’s what a first sergeant was basically doing. It was all about discipline. They would select first sergeants by getting the biggest, meanest, ugliest guy they could in the squadron. They put a diamond on their sleeve above their stripe. They might be a staff sergeant or a technical sergeant—there was no requirement to be a senior noncommissioned officer.

As I came through the ranks, I watched how first sergeants dealt with things, and I kept an eye on their career field. When we became a volunteer force, the role of the first sergeant began to evolve to where we are today. No longer spending an inordinate amount of time on disciplinary actions, they can commit themselves to taking care of their Airmen and their families. They can now focus on quality of life concerns and professional development.

When I became the CMSAF, I was fundamentally the functional manager for first sergeants, and I took their role very seriously. I would often remind them, “No Airman deserves to live in a dormitory where inmates run the asylum. You need to visit your dorm at two o’clock in the morning on a weekend and find out who has their music cranked up and disturbing their teammates. Seek out the ‘disrupters.’ You need to see if there’s that smell of marijuana. Then you need to discipline them.” I reminded first sergeants that they owned the dormitory. The job of the dormitory manager is to make sure everyone has their supplies. It’s the job of the first sergeant to enforce the discipline and make sure the rooms are kept clean and neat to avoid insect and vermin infestations. Some first sergeants believe in a hands-off approach. They will say, “Well, they deserve to live without a mom and dad watching them all the time.” That approach seldom works. It is a communal living environment, and it’s critical the living and cleanliness standards be very high. You have to inspect the rooms to make sure everybody has a safe, quiet place to live. I always liked the ABC approach. If you earn an “A” room, you get inspected once a month. You earn a “B” room, and you get inspected every two weeks. You get a “C” room, and you get inspected daily until you bring it up to an acceptable standard. And the knuckleheads who can’t keep their stereo turned down, you get your stuff locked up until you learn how to not disturb your teammates.

So my experience in my formative Airman years in Taiwan and Vietnam made a difference in how I view the world—especially first sergeants. In retrospect, I know the leadership in Taiwan and Vietnam didn’t come to visit our barracks because they were afraid. It was like going inside San Quentin.

You eventually left Vietnam. The last combat troops left 29 March 1973, and a few months prior, the draft ended. What do you recall about that transition and that culture shift?

Our Vietnam prisoners of war [POW] were released in 1973 and went through a yearlong repatriation process before entering back into the Air Force. I was a young staff sergeant at Bergstrom AFB in Austin, Texas, assigned to the 67th Tactical Reconnaissance Wing. One day I was introduced to my new boss, Col George Hall, who had been shot down as a young captain and spent nearly eight years in captivity. Also assigned to Bergstrom were other POWs I would get to know, including Col Terry Uyeyama, Col Scotty Morgan, Col John Stavast, Col Walt Stischer, and Lt Col Al Myer. I could never do justice in describing the impact they had on me. All of them had spent five or more years as captives of the North Vietnamese. They were brutally tortured, spent years in isolation and deprived of decent food and shelter. I listened intently to their stories. In the end, I would never complain about where I slept or what I had to eat ever again. They are heroes—they were not given the welcome home they deserved. And yes, I am NOT a fan of Jane Fonda and a few others from that era.

I also cannot say enough about the end of the draft and the all-volunteer force. Having all volunteers allowed us to focus on becoming “professional Airmen” and greatly improving our readiness and combat capabilities.

Did you find that Airmen struggled to transition to an in-garrison force? If you relate it to where we are today—we have a lot of Airmen who are used to deploying and fighting; that’s all they know. Then you start to transition out of that into a garrison force. Did you find that was a difficult transition for them?

We had three periods that were very distinct for me during my tenure. We went through the ’70s, which of course was the Vietnam War. When I came in, our force was probably at 850,000. We were putting somewhere between 70,000 and 80,000 troops a year through basic training. Now it’s down to 30,000 or so. So we went through the era of the draft. Then we started transitioning to the volunteer force. In the late ’70s, under the Pres. Jimmy Carter administration, we wound up with what would be called a “hollow force.” We weren’t funded properly. We didn’t have the money to do training. The administration’s focus was not on the military; it was on social and economic issues.

Then in the ’80s, when Pres. Ronald Reagan came on board, very generous pay raises and other funding became much better. It was a complete 180 turnaround compared to what we had endured under Carter. Reagan’s idea was to build a military that was so strong it would cause the Russians to fold—to collapse internally because they couldn’t keep up. They would have to spend so much money to keep up with us militarily that they would collapse. And it worked. So during the ’80s, we had all the people we needed. We had too many people to be honest with you. We had the assistant to the assistant NCOIC [noncommissioned officer in change]. Sometimes you would work three or four days a week. Weekends were yours. We were seldom deploying, and even those deployments affected a small number of career fields. We had a very large presence in Europe, with hundreds of installations. With that forward presence, there was little need to deploy.

Then the wall comes down in 1989, and that changed everything. Suddenly, we found ourselves in a draw-down mode. We were no longer absorbed with the notion we would be fighting the Soviet Union, and we certainly did not need that large presence of Airmen in Europe. So, we did a massive pull back, and eventually reduced to six main operating bases. Along with the large installations, we closed countless geographically separated units. That was huge. Stateside, 30 percent or so of the bases closed. The drastic reductions were under the Pres. George H. W. Bush administration.

In 1991 Desert Storm and the first Gulf War kicked off. Because we had taken down so many infrastructures in Europe, we found ourselves supporting operations more and more from CONUS [continental United States]. Following the liberation of Kuwait, we established two no-fly zones in Iraq: one supported from Prince Sultan AB, in Saudi Arabia, and the other from Incirlik AB, Turkey. We would enforce these no-fly zones until 2003 when Saddam Hussein was eventually taken out of the picture. You can imagine the number of sorties being flown for more than a decade of air operations and the amount of Airmen who would contribute to those missions. We had somewhere between 15 percent and 20 percent of our force deploying constantly to Saudi Arabia and other locations in the Middle East to support that effort. This was a big mind-set change as our Airmen began to deploy for 120 days, be back home for a short period of time, only to find themselves deploying again. It caused a lot of turmoil for our families.

This was new for me as well. In 1991 I was a new chief master sergeant and had a NATO assignment—the Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe in Belgium. I had 73 administrators working for me at the time, and we were just beginning to have conversations about becoming a more expeditionary force. In 1993 I became the 12th Air Force senior enlisted advisor to Lt Gen Jim Jamerson at Davis-Monthan AFB, Arizona. We had 10 wings and a USSOUTHCOM [US Southern Command] mission, supporting counterdrug operations. The notorious Columbian drug kingpin Pablo Escobar had just been killed; so, it was a busy time in South America. Twelfth Air Force was supporting the counterdrug effort at locations in Columbia, Ecuador, and Peru. I would travel to visit them via Howard AFB in Panama. It was eye opening to visit Airmen at these forward deployed and very austere locations, and it was critically important that we support them and provide anything they might need on a moment’s notice. Potable drinking water was at a premium, and it was essential their food supply be sustained without interruption. It was also becoming readily apparent that deployment after deployment by some of our career fields was taking a toll on families and retention. By the time I became the United States Air Force in Europe (USAFE) senior enlisted advisor in 1994, we were deploying our Airmen in earnest—many of them from fighter bases like Spangdahlem AB, Germany, and out of bases in the UK [United Kingdom]. I was leading Airmen who would say, “Chief, I didn’t sign up to be in Saudi Arabia twice this year.” A lot of them were security forces, support personnel, and maintainers. It was just a small number of career fields, and we were abusing them. We were using them too much. The majority of the force was not identified as deployable; so, the same people were going time and time again.

At the same time, our operations tempo was increasing and we were becoming more expeditionary, the United States was enjoying a very robust economy. The “dot.com” boom was happening, among other things, and employment was easily obtained—especially if you were a drug-free, disciplined veteran. This gave our folks a lot of options. We became a recruiting pool for the private sector. We would train them, and the private sector would lure them away from us. The dissatisfaction with the change of the health care system to TRICARE and its associated growing pains, increased numbers of deployments, a retirement system that seemed unfair to those who joined after 1986, and family separation created the perfect story for retention issues. Spouses were saying, “Hey, look, I’m done. I’m tired of raising the kids by myself. You’re always over in Saudi Arabia. And when you come back, they give you a one-year assignment to Kunsan, Korea.” There was a lot of dissatisfaction.

Gen. Ron Fogleman started to draw up the Expeditionary Air Force, and of course, that transitioned to Gen. Mike Ryan who completed the process. Instead of 15 percent to 20 percent of our Airmen deploying for almost all of our force, about 95 percent to 96 percent of our force was now identified for deployment. They developed the Air Expeditionary Force concept. That would begin to shift the deployment responsibility tremendously.

But we also had to address a cultural shift. Those who had spent their entire careers in an in-garrison posture, where we never deployed, were fomenting a lot of the dissatisfaction. They were focused too much on their pay and benefits. They were losing sight of the real reason we serve in uniform, and it was a time to get back to basics. It was about wearing the uniform, the missions we do in preserving our freedom and liberty, and supporting others who serve.

After the war ended, you volunteered and went to Grisham AFB, Indiana. I think you were a senior airman then and, as I understand it, really made a mark on your unit. I found that interesting, because many would say that as a young Airman you can’t have that sort of influence. Why did you have that influence?

Well, first of all, I was never a senior airman—I was a sergeant. A senior airman was only created as an additional grade to keep the amount of enlisted people or noncommissioned officers below the congressional limit. So, I was a sergeant, and I was always looking forward to work on the flight line. But I happened to be the lucky person. They assigned me to field maintenance to handle logistics and technical orders. I worked with quality control to put together deployment kits for cold weather deployments—tool kits and all that type of stuff. I learned how to handle a budget and started using a computer—a Burroughs 3500. I was like a jack-of-all-trades; so, they pulled me away from the flight line to go work in field maintenance and work in their logistics division. I learned an awful lot there. Of course, while you’re learning, you’re always trying to do your best, and fortunately, I was able to have an impact on the unit.

Quite honestly, I got tired of talking about how much pay somebody was going to make on the outside. I would finally just say, “Obviously, you are not happy with the Air Force and want to pursue other options, and to that I would say, ‘Thanks for your service, and I wish you all the best.’” Then there was a perception that they had this massive erosion in benefits. Everywhere I went, I would have people tell me our benefits were eroding massively. When I challenged them to name me five benefits and five entitlements or just tell me the difference between a benefit and an entitlement, they just stared at me. The facts were that we had gained tremendously in pay, benefits, and entitlements over the years. But the perception became reality—and for the first time in decades, we were having problems with retention in all three categories—first term, second term, and career. And for the very first time, we had to allocate millions of dollars toward recruiting marketing.

So as you can see, each decade was tremendously different. The turmoil of the ’70s and moving from a draft force to the all-volunteer force; the blissful ’80s, when we had very few deployments and lots of resources; to the very volatile and under-resourced ’90s, when we had to become expeditionary.

You mentioned your NATO assignment in Belgium. That was in the late ’80s to early ’90s, right after the Cold War and into the Gulf War. You were working with 16 different nations, the different services. What did that teach you about our ability to fight as a combined and joint force?

NATO was very interesting. I worked at SHAPE headquarters, Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe. Some people said it really stood for Super Holiday at Public Expense, but it really wasn’t. NATO was there to fight communism, and to join together if the Russians ever came across the Fulda Gap with their tanks.9 I think we worked well together. Every nation had a vote on how we did things. There were different beliefs, different ideas, different cultures, and it all came together there. If there was a serious issue, there would be infighting. The French would disagree with what the Dutch said, or the Dutch would disagree with what the Greeks said. The Greeks and the Turks didn’t like each other. There was a lot of that kind of drama, but if they ever had to coalesce to fight a common enemy, I am confident they would have done that very well.

It also showed me that America leads the way in NATO. The American contingent did the bulk of the work, along with the Brits and Germans. That’s just the way it is culturally. I had an interesting encounter with a Turkish brigadier general. I had 73 administrators, so I had Dutch, Greeks, Italians, Americans, British, US Army, US Navy—a cultural blend of different administrators and different capabilities. This Turkish general had a Dutch E-7 and an Italian E-9 as his administrators. Turkish generals did not talk to the enlisted. Their enlisted force was made up of conscripts who made the coffee, drove the cars, and did other mundane things. One day I was in my office and was having a counseling session with somebody. The door opened, and in walked the Turkish general. I’m thinking, “Oh, my gosh—this never happens.” If he saw me in the hallway, he wouldn’t acknowledge my presence. I’m a chief, and he still didn’t talk to me. But he came into my office, he looked down at the person on the chair and nodded for them to leave the room. The person left, and the general sat down and said, “Chief, I want to make you a proposition.” I said, “What proposition would that be, general?” He said, “I want to make a trade.” “What would that trade be?” “I want to trade one Dutch E-7 and one Italian E-9, for one US Air Force E-4.” I smiled to myself, and at the same time was flush with pride. That encounter was proof positive of our capabilities and how respected our Airmen truly are. Of course, I didn’t make the trade, because no one was willing to give up their Airman. Our administrators could do all kinds of things. We were just beginning to get computers, and our Airmen were just burning it up. So, here this Turkish general wanted to come down and make a trade—two very senior enlisted for one US Air Force E-4. Pretty much says it all.

Absolutely. You were there when the Berlin Wall came down—the end of the Cold War. You talked a little about the impact that had on our Air Force going into the ’90s. What can you say about the overall sentiment when the wall came down and the Cold War was over?

The possibility that we would have to fight the Russians in the Fulda Gap and elsewhere in Europe tank-to-tank created a very tense environment for all of the involved nations. It could have happened at any moment, and you never knew. There was a lot of tension of course, but when Reagan came over and told [Mikhail] Gorbachev to “tear down the wall,” it really set things in motion. It just happened. One day we were poised for a horrific war and horrific conflict all across Europe, and the next day they had sledgehammers and were taking down the wall. You sat back and went, “Holy cow.”

NATO was a full-up force, with all the nations contributing manpower. Suddenly, it seemed the reason for NATO went away. Without communism and the Soviet Union staring at us through the Berlin Wall, was there really a reason for NATO to exist? We were knee-deep in classified plans for these battles, and then it was gone. We didn’t have an enemy anymore. People were saying, “Why do we need NATO anymore? Perhaps it is time to rethink our individual contributions to NATO in terms of manpower and resources.” Immediately, a lot of the nations started saying, “I’m not going to give you 15 people anymore. I’m only going to give you five.” They immediately began to draw back on NATO personnel commitments. Had it not been for Saddam Hussein and the first Gulf War, I believe there would have been a serious effort to dismantle NATO. Saddam brought reality to the world situation—there are still a lot of bad guys out there, and we need to stick together in the fight against them.

As a part of that evolution, a lot of former Eastern Bloc nations wanted to become part of NATO. We started having peacekeeping discussions and created Partnership for Peace. Of great interest to the former Eastern Bloc nations was our enlisted force. They had great difficulty in comprehending the concept of a professional NCO corps. We invited them to visit the Kisling NCO Academy [Ramstein AB, Germany]—giving them a tour of the facility and briefings on our curriculum and teaching methodology. Numerous flag officers and their staffs would attend. After the tour and briefings, they would sit down with several of the students and faculty. They sat down and asked, “What do you do?” And our student would say something like, “Well I have a bachelor’s degree, and I work in finance.” They went to the next person and asked, “Well what do you do?” “I maintain F-16 aircraft. I have an associate’s degree, and I am working on my bachelor’s degree.” They would go around the room, getting similar responses from each of the students. I could see they were mesmerized at the education levels and the technical qualifications. Some actually thought we were lying to them. In their services, a major would be working maintenance, not an enlisted person. Their enlisted force would be primarily made up of conscripts and relegated to more menial duties. It was our philosophy that if we could somehow influence the culture of their services and plant the idea of developing a professional NCO corps—then NATO as a whole would be much better for it. We began sending Air Force enlisted instructors on temporary duty to Albania, Czechoslovakia, and many other countries to work with their armed forces and help them develop a professional enlisted force.

It’s a culture thing, and it’s very difficult to replicate. It is what makes us who we are as an Air Force. The professional NCO corps we have—the enlisted force we have—is so much better than any other country on this planet. That’s what makes us the best.

You were the USAFE senior enlisted advisor during the mid-90s. You mentioned the no-fly zones, and there was Provide Comfort, Deny Flight, Deliberate Force, and other operations...we were very busy at that time. What do you remember about the impact it had on the Airmen?

My USAFE assignment was a very busy time for me. In my 18 months as the USAFE senior enlisted advisor, I worked for three four-star generals—Gen Jim Jamerson, who hired me initially and then went to EUCOM [European Command]; Gen Dick Hawley, who joined us from the Air Staff in the Pentagon would be there for roughly seven months before becoming the Air Combat Command commander; and Gen Mike Ryan, who would come to USAFE from 16th Air Force. All of them had a different temperament and a different philosophy. But they had one thing in common—they were extraordinarily concerned for the welfare of their Airmen and their quality of life. I’ll never forget General Hawley’s comment, “We do not have congressional representation in Europe—there is no senator or representative who has Europe as part of their constituency. Therefore, I will ensure they visit us and take back with them our requests for more money to work our infrastructure and other issues.” Europe had been neglected after the draw down, so there were lots of lucrative targets to fix. They were all concerned with making improvements, because after the draw down, Europe was neglected. While the Air Force was chasing one-plus-one dormitories, we had 30 percent of the Air Force’s gang latrines in Europe. I am particularly proud of our efforts in this area. We put together a dorm council, made up of the numbered air force senior enlisted advisors and myself, and chaired by the vice commander, Lt Gen Everett Pratt. The team developed a history on each dorm, plotted out the necessary improvements and cost, and then presented it to the USAFE commander. Within a few years, there were no more gang latrines in Europe—all were in the one-plus-one configuration. We were able to bring Congressional leadership to the theatre. We took them into the gang latrines and had them stand in the middle of the mess, where the mildew, the mold, and the infrastructure was decaying. We had them experience it firsthand; so, when they went back they would put a wedge of money in the budget for quality of life for USAFE and Europe. We started Aviano 2000 in 1995, which was basically a complete overhaul of the infrastructure and quality of life issues at Aviano AB, Italy. Quality of life—that was our primary focus.

In the middle of all that, President [William] Clinton decided we were going to stop the fighting between the Serbs and the Croats. We were going to stop the ethnic cleansing and all the bad stuff that was happening over there with [Slobodan] Milosevic.12 So the president put together the framework for the Bosnia Peacekeeping Mission.13 We we’re sitting in the Tunner Conference Room at USAFE Headquarters, and General Hawley was directing how the air bridge operations would work in Tuzla, Bosnia. We were going to build an air bridge for our airlifters, primarily C-17s [Globemaster III transports], to bring in tons of equipment and personnel to support the effort. They were going to stage out of Tuzla and push forward to develop a zone of separation that would consist of multiple checkpoints. It was going to be a massive operation in terms of airlift tonnage and manpower.

General Hawley went around the conference room and queried all his officers on how things were going to work. Then he got to me and said, “Chief, I’ve got my commander. I know who I’m going to send. Who’s going to be the first sergeant?” And I said, “Sir, I’ll have to get back with you on that.” He went on to explain, “Tuzla has an abandoned Russian air base. We’ll quarter the troops in the abandoned buildings until we can get the tent city built. A Red Horse unit will do that for us. Everyone will be armored up with a flak jacket, helmet, and they will carry a loaded M-16. They’ll be subsisting on MREs [meals, ready to eat] every day. It’s going to be in December [1995], so it’s going to be extremely cold. You’re going to need somebody who can take care of all those things.”

We had not quite developed into the expeditionary mind-set, so I was very concerned with finding someone qualified to lead an expeditionary adventure such as this. I went upstairs to my office and called all the senior enlisted advisors and presented them the scenario. I said, “Guys, I need a tough, no-nonsense first sergeant who can handle a deployment like this under these conditions.” CMSgt Bill Jennings at 17th Air Force called me back, and he said, “I’ve got a guy I’m going to send over to see you.” I asked, “What’s his rank?” He said, “A master sergeant.” I haltingly said, “Master sergeant?” Bill said, “Yeah, he’s young, but he’s good.” I asked, “What are his qualifications?” “He’ll tell you when he gets there.”

Shortly thereafter a young master sergeant named Tim Gaines showed up at my office. I skipped the formalities and immediately said, “So, Tim, tell me why you’re qualified to lead this deployment?” He said, “Well, Chief, I’m the first sergeant for 1st Combat Comm [Communications] outfit. We actually deploy every so often and spend a lot of time on the road. We’re one of the few units in the Air Force that deploy quite a bit, setting up communications at various locations. We live in tents. Our gear includes helmets and flak jackets.” I was very uneasy, but it was obvious I wasn’t going to get anyone else who could speak the language of regarding deployments.

“All right, Tim. You’re the guy. I’m going to send you in there.” Then I said, “The first thing I want you to do when you get to Tuzla is find the command sergeant major for the First Armored Division. I want you to stay close to him, take his mentorship, take his leadership, and use it. He knows how to handle troops who have weapons, and he knows about the explosive mines problem, etc. He’s a seasoned war veteran and an expert regarding this kind of environment.” His name was Jack Tilley, and he would eventually become the Sergeant Major of the Army.

I was extremely nervous about sending a young master sergeant to do this job. Seriously, I wanted to take it on myself. I told Tim that General Hawley and I would be down there in the next 30 days and that if he needed anything at all to let me know and I would be on the first C-130 out of Ramstein. He very confidently said, “Okay, Chief,” and he left my office. I had tasked him with bedding down the troops in a cold and hostile environment; charged him with the health and welfare of all the Airmen at Tuzla. That included keeping them quartered in abandoned buildings, keeping them fed, and keeping them motivated. He also had to ensure no one mishandled their weapon and kept them secure. The Army was going to be rolling through Tuzla in Humvees, tanks, and in the large M2 Bradleys. It was very possible for someone to get run over, especially in the dark.

So MSgt Tim Gaines headed down to Tuzla, and within days I was getting e-mails. I was expecting a full plate of problems and issues. Instead he said, “Hey, Chief, can you send me down some washers and dryers? I want to set up a laundromat so our Airmen can wash and dry their uniforms. The contractor who is supposed to do it [Brown and Root] can’t keep up with the demand. Also, can you send some board games—checkers, chess, Monopoly—that kind of stuff?”

I’m thinking, “Wait, a minute. Didn’t I send you to a combat zone? Shouldn’t I be getting frantic e-mails with casualty lists and other bad stuff?” Instead, he said, “Chief, we have things under control.” Tim had already established a Top III organization to help him run things. They were conducting reenlistment ceremonies at the flagpole. All the senior NCOs had bonded together under his leadership and were functioning as a well-oiled machine. He had made the connection with Jack Tilley, the 1st Armored Division command sergeant major as well. Jack was giving him tons of mentorship and helping him succeed. They were having reenlistments at the flagpole. I was very pleasantly surprised at how well our Air Force team was functioning—far exceeding my expectations. Everyone was pulling together; no one was complaining, and no one wanted to leave. It was just phenomenal. It was one of the proudest moments of my life.

I told Tim, “I’m only going to leave you there for 60 days.” Being part of the initial cadre, I knew he was working exceptionally long hours, and eventually, he would succumb to the fatigue. I also wanted to rotate as many first sergeants through Tuzla and other locations as possible to give them firsthand deployment experience. A normal rotation was 90 to 120, depending on the position. I brought him out after 60 days, and then I sent in another first sergeant, MSgt Terry Spears, who also did a magnificent job and built on Tim’s success. Every day it was getting better and better. Red Horse came in and did a tremendous job in building a tent city with heating and air conditioning for our Airmen. I sent in MSgt Jeff Gryczewski to replace Terry Spears. Jeff was a highly motivated first sergeant with a security forces background. He continued to build on the tremendous foundation that Tim and Terry had laid. Every first sergeant that worked the Bosnia effort made chief—with the exception of Tim who opted to retire as a senior master sergeant. I am extremely proud of all of them to this day. They were phenomenal leaders and did exactly what first sergeants should do.

The whole idea was to get that experience and capture it. I said, “I want trip reports; I want you to build detailed trip reports on what works and what doesn’t so that your successor can more easily build upon your work.” I took all of those reports and sent them to the First Sergeant Academy. The trip reports would be folded into the curriculum at the Academy, making it more realistic.

It sounds like that experience was one that highlighted the need for the Air Force to shift toward that expeditionary mind-set.

Absolutely. That was a big part of it. You could tell the difference between a first sergeant who knew how to deploy and one that didn’t. It began the warrior Airman mentality and mind-set—critical to being able to function in a combat environment.

The culture of the First Sergeant Academy was critical to me, and I wanted to institute some changes shortly after I arrived at the Pentagon. As timing would have it, the commandant was getting ready to depart. I had met a very impressive first sergeant at Andrews [AFB, Maryland] named Roger Ball. Roger was a recently promoted chief. He had also just moved to Scott AFB, Illinois, and had only been there a few months. I called him and said, “Roger—I need you to be the commandant at the First Sergeant Academy. Will you consider it?” Without hesitation, he said, “Yes.” This was service before self personified. He could have easily said, “Chief, I just moved, and it’s going to be hard on me and the family.” Instead he stepped up.

One thing in particular bothered me. We would select someone to be a first sergeant at their home station and allow them to immediately wear the diamond, without having completed the school. It created a culture of “I’m already a shirt, you can’t teach me anything” attitude. Chief Ball stopped that immediately—you had to earn your diamond, and there would be a formal graduation ceremony to recognize your achievement. You come to the school, you learn, and you get scrutinized by the Academy staff before we allow you to wear the diamond. And that night you graduate—it’s special and something you won’t forget.

The fact that we add the diamond in your chevron, what does that mean? Airmen don’t care about your AFSC or your specialty badge. You can take your badge off, because now you’re a first sergeant. The diamond means everything. When somebody looks across the room and they see the diamond on your sleeve, there’s an expectation. There’s an expectation that you set the standard, that you’re the leader, that you’re the one in charge of the discipline and the health and welfare of the troops. You can’t take that lightly. You can’t just put that diamond on without having completed the course and gone through the crucible of becoming a first sergeant. When you step across the stage and everybody claps for you and praises you for all the good things you’ve done to pass the school, it needs to be a significant emotional event for you. It needs to set the tone for how you’re going to behave and act as a first sergeant. I thought that was critical.

My early years and the lack of interaction with my first sergeants certainly impacted my view of the career field. I was tough on them—you have to be, because they have so much impact on our Airmen. And if they don’t do it right, they can do a lot of damage. Nothing worse than a bad first sergeant.

You also focused on education and development quite a bit. At USAFE you created the NCO professional development seminar, which exists at most bases today in some form. Why was it important to build that seminar in between the PME [professional military education] that already existed?

The first professional development seminar I conducted was at SHAPE. Many of the noncommissioned officers there had lost their blue and were forgetting fundamental military discipline. I found there were a lot of people on those assignments who would extend and stay forever. I also recognized there were wide gaps between the time someone attended Airman Leadership School [ALS] and the NCO Academy. There might be a 10-year gap where someone’s professional development went into the idle mode. Following graduation from ALS you would be pumped up, reinvigorated, and re-blued. That would begin to fade as years went by prior to attending the NCO Academy. So the Professional Development Seminar was created to fill that gap—to take staff sergeants out of their workplace for a week and re-blue them. The effort at SHAPE was a much smaller scale than the ones we conducted at Ramstein. A lot of tremendous senior NCOs and officers participated, developing a locally based curriculum and agenda that directly tied to the mission. It gave young NCOs the big picture and access to personnel information and other material that they would not normally have on a day-to-day basis. It was information they could use to mentor their subordinates. The seminar was about Airmen taking care of Airmen. As part of the program, we would take support personnel (finance, personnel, etc.) down to the flight line and have them spend time with a crew chief. They would then appreciate the operational side of the mission. We even gave them a ride in the back of a C-130. All good stuff.

The first time it was just an informal thing. I got all the senior NCOs together, and I said, “Okay, let’s build a day-long seminar, and let’s address values. Let’s address professionalism. Let’s address how all this applies to the mission.” Senior NCOs volunteered their time to make presentations. We also had a first sergeant’s panel and a chief’s panel. At the end of the week, the USAFE commander would address the students. We filled the Tunner Conference Room with eager staff sergeants. All of our senior NCOs wanted to be engaged; they wanted to be involved. They said, “Hey, Chief, I’ll brief this, and I’ll brief that.” It brought the senior NCOs and junior NCOs together. It enhanced the communication.

Each time it got better and better. Then they tried to make it more sophisticated. Next thing I knew, I had NCO Academy instructors that wanted to do it. They wanted to come over and formalize it. I said, “No, no, no. I don’t want to formalize it. I don’t want professional instructors doing this. It is not another level of professional military education. I want that master sergeant or that senior master sergeant from maintenance to come over here and get in front of 150 staff sergeants. I want them to have that experience, and learn from that experience.”

That’s how it started. We started the more formal process at Ramstein AB, and I had all of the main operating bases establish one as well. When I became the CMSAF, I made it mandatory for all installations.

It shows how much you championed education and development, both PME and other sources. Why was that so important to you?

If you’re going to have a professional NCO corps, then you have to focus on professional development. In addition to the formal education you get from the professional military education, you must fill those gaps in between. There is a tendency to become complacent and allow standards to become lax. That is when bad things happen. The professional development seminars helped sustain that focus on professional development.

You were the Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force when we established our Air Force Core Values—Integrity First, Service before Self, and Excellence in All We Do. You helped introduce the Little Blue Book. What was the impetus behind those values and that book?

Unfortunately, our core values were released following some very tragic things that happened in our Air Force between the years 1994 and 1996. The first was the Black Hawk incident that took place on the Iraqi border in April 1994 as we were enforcing the no-fly zone as part of Operation Northern Watch. Two F-15s being controlled by an AWACS [Airborne Warning and Control System] aircraft misidentified and confused two US Army Black Hawks with what they thought were Soviet Hind helicopters and shot them down. A total of 26 people were killed—including French, Kurdish, US, etc. The helicopter mission, known as Eagle Flight, had been conducted by the Army for three years prior to the incident. On this particular day, the AWACS, for whatever reason, didn’t control the airspace properly. Initially, the pilots were charged with criminally negligent homicide, and several of the AWACS crewmembers were charged with dereliction of duty. Eventually, all charges were dropped with the exception of one AWACS crewmember, who was eventually acquitted at a court martial.

Bottom line—26 people killed, and no one was going to be held accountable. The investigation found multiple problems—the missions had not been integrated, even though Eagle Flight and the fighters had been in the same air space for more than three years; there was no preflight discussion regarding the possibility of friendlies in the same space; and the AWACS had fundamentally lost control of the mission. I believe they were only controlling four aircraft that day. Training and a lack of understanding on whether they were responsible for the helicopters was also an issue. In other words, there were a lot of mistakes and errors made. But the commanders in the chain of command failed to take any disciplinary action, nor did they hold people accountable in any way.

The lack of accountability did not set well with the Chief of Staff, General Fogleman. He would subsequently release an Accountability videotape for all officers and senior NCOs to view. In it, he admonished leadership that just because no one was sent to prison for their negligence, their actions did not meet Air Force standards—that the American people hold us to a higher standard. In the end, he disqualified crew members; placed disciplinary letters in the crew members’ records, and rescinded any pending PCS decorations. The actions included general officers. For the Chief of Staff to personally discipline individuals in the chain of command of other MAJCOM [major command] and subordinate commanders is unprecedented.

The second incident involved a B-52 crash that took place in June of 1994 at Fairchild AFB, Washington, just a couple of months after the Black Hawk incident. A B-52 with four crewmembers on board was completing a practice flight for an air show that would occur the next day. At the conclusion of the practice, the pilot requested approval from the tower to land. As he turned toward making his final approach, he banked the aircraft past 90 degrees without sufficient airspeed or altitude to sustain flight. They crashed, resulting in a huge fireball and killing all four crewmembers. It was another tragedy that did not have to occur. It was the vice commander’s final flight before retirement; so, a lot of family and friends were on hand to celebrate. Instead, they witnessed a horrible tragedy.

The subsequent investigation concluded the accident was the result of the “pilot’s aggressive personality.” Further investigation revealed the pilot had six major flight violations in the past three years—any one of which should have disqualified him. Instead, the 10 colonels in the chain of command who had the moral obligation and responsibility failed to take him out of the airplane. The squadron commander had been lobbied by his junior pilots to disqualify him and attempted to do so with the director of operations, only to be told it would not happen. The only reason the squadron commander was on the plane that day was because he would not allow any of his subordinates to fly with that individual.

Bottom line—the pilot had a history of being unsafe, of being obnoxious, and undisciplined. Leadership failed and did not take the appropriate action, and if they had, this incident would have been prevented. Another tragedy that did not have to happen, and a lesson for all Airmen to speak up when you see something wrong and take action—and if you are a leader, you better be listening to your Airmen.

First the tragic shoot-down of friendly Black Hawk helicopters, followed by the tragedy of the B-52 crash at Fairchild, and we would have yet another tragic incident in April of 1996. Secretary of Commerce Ron Brown, a charismatic public servant with excellent diplomatic skills, was a political appointee of President Clinton. The president had asked him to go to the Balkans on a diplomatic mission, which would originate at Ramstein AB, Germany. Following the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, a lot of former Eastern Bloc nations wanted to be considered for entrance into NATO. Keep in mind, we had recently established the air bridge at Tuzla, Bosnia, so there was a lot of activity in this region of the world. I was the USAFE senior enlisted advisor at the time.

The aircraft to be used was our CT-43 commercial type aircraft, which had been modified for VIP [very important persons] travel. It had a food galley and was very comfortable. We would use it when the commander and I would travel long distances to visit deployed Airmen, and typically a large contingent of personnel would accompany us. The aircraft fell under the operational control of the 86th Wing commander at Ramstein.

Ron Brown wanted to go to Tuzla, Bosnia; Zagreb, Croatia; and then on to Dubrovnik, Croatia. Unfortunately, they crashed 1.6 miles off course. They crashed into the mountain and killed all 35 souls on board. Initially, one of the flight attendants survived because she was seated in the rear of the aircraft, but her wounds would prove to be mortal. The location of the crash was very remote, and it took several hours for our special operations team and the Croatian army to find it.

The investigation found multiple errors made by the crew; that there was some bad weather in the area, which was a distraction; and the Dubrovnik airport lacked sophisticated navigation equipment to support landings and aircraft control. They were relying on beacon technology. The accumulation of crew mistakes, outdated navigation technology, weather, and other causes meant the aircraft was doomed to crash.

But what is most important to know—the aircraft never should have been there. Air Mobility Command [AMC] had said, “No Department of Defense aircraft will fly into Dubrovnik, Croatia.” The wing leadership knew this, but they wanted to do the mission badly. After all, we are the United States Air Force, and we can do anything. We’ve flown into this location previously; so, we knew how to do it. And besides, we are supporting the president of the United States, and if he wants a diplomat to go to Dubrovnik, then we’ll make it happen. So, the wing leadership requested a waiver from Air Mobility Command. However, AMC came back with a “no” and disapproved the request. They went ahead and did the mission anyway.

Sixteen officers were disciplined—this included the immediate firing of the wing commander, vice commander, and ops group commander. A flag officer at USAFE was disciplined as well. We disciplined a flag officer in USAFE as well—a total of 16 officers.

Regardless of the circumstances, you must follow the rules. They exist for a reason. The leadership at the wing did not have the authority to ignore or overrule the guidance from Air Mobility Command. Had they played by the rules, this tragedy would never have occurred and everyone would be alive today.

I took this tragedy personally. We had flown with these crew members, and the enlisted members had recently participated in my professional development seminar. Attending their funeral services and seeing their children and family members grieve for them broke my heart. I felt a personal responsibility for them—after all I held a senior leadership position within the command. I didn’t have operational responsibility, but it still weighs heavily on my mind.

These tragic incidents and a few other personal failures were having a negative impact on our Air Force. In General Fogleman’s mind, we had lost our way and we were making too many catastrophic mistakes. Leadership was failing.

Gen William Tecumseh Sherman, the famed Union Civil War general, was quoted as saying, “Every Army has a soul, just as a man has a soul. A commander must command the soul as well as his men.” The Air Force has a soul and spirit that is the aggregation of all of our hearts, minds, and spirits. To be a great leader, you have to recognize when that soul or spirit is in trouble. General Fogleman did just that—he knew he had to get the force back to basics.

According to an article by Gen Mike Ryan, published by Air University, the Air Force had core values as far back as the ’70s. But I don’t believe they were ever really codified. And there were more than three. I joined the Air Force in 1970, and other than being taught that values and how you conduct yourself matter, I do not recall any focus on core values. I am sure they existed, but they were obviously marginalized and not inculcated into our culture. General Fogleman took a look at this, and he thought, the Army had seven and they were all tied to the word leadership. The Navy and the Marine Corps had honor, courage, and commitment. He took a really hard look at this and came up with integrity, service, and excellence. He felt all the core values from the other services fit under those three, and that was all we needed. He didn’t want to complicate it; he didn’t want to make it something you had to work to memorize. He wanted the values to be in your heart and drive your behavior.

In 1997 we released the Little Blue Book. We did a massive campaign effort to get them in the hearts and minds of every Airman. I did a videotape speaking to the core values that was looped on television sets at Lackland AFB basic training. So, while the trainees were standing in line at the dining facility, they would see me discussing core values. We also issued the Little Blue Book to every Airman and began discussing them at all levels of enlisted professional military education—to include ALS, NCOA, First Sergeant Academy, SNCO Academy, Air Force ROTC [Reserve Officer Training Corps], and the Air Force Academy, etc. General Fogleman reminded us that the tools of our trade are lethal. We are not a private industry or corporation that can afford not to live by values—they must be part of our DNA—Americans expect a higher standard, and we must live up to that standard. Live your life with your core values as your guiding light, and you will always do the right thing—even when no one is looking.

Looking back now, it’s been almost 20 years since we identified and began inculcating our core values. Today, every Airman knows the core values. How do you think they’ve impacted the force we have today?

I’ll give you an example. The company I work for is USAA. I think everybody in the military probably knows who they are. They have core values: honesty, integrity, loyalty, and service. It’s a company that has been around for over 90 years, and it does extremely well. Then you look at a company like Enron that, probably, didn’t have core values, or at least didn’t create a culture that lived by those values. I think a lot of companies fail because they don’t recognize their organization has that soul and spirit. If you don’t stay on top of that, things will fail.

It’s the same way with the Air Force. I truly believe the vast majority of our Airmen today come to work every day with that kind of attitude, but we have to constantly reinforce the value.

The Air Force recently released an updated Little Blue Book. It focuses on the profession of arms and includes the core values as well as the oaths, the creeds, etc. Would you say it’s important to evolve and reinforce that mind-set in new ways?

Absolutely. I am especially pleased with the new version of the Little Blue Book called the Profession of Arms. Not only does it include the core values, but also the oath of enlistment, the code of conduct, and the Air Force Creed. All of these complement each other. It’s a great evolution by General Welsh and Chief Cody and will serve us well.

One of the things you did as the Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force was lead the change from the title senior enlisted advisor to command chief master sergeant, which included the new chevron. Why was that change important to you?

When I came into the Air Force back in 1970, the top chief on the base was known as the wing sergeant major. He sat in a prominent position within the headquarters, typically just outside the offices of the wing commander and the vice wing commander. The title was a throwback to the Army Air Corps days. But I really liked that title because it represented authority and strength. I recall my squadron commander’s reaction when he learned the wing sergeant major would be visiting his unit. He ordered everyone to clean up their areas, and anyone who needed a haircut should leave the building. The wing sergeant major had that kind of impact.

At some point the Air Force opted to abandon the title, which of course was the right thing to do. After a lot of back and forth between the Pentagon and the MAJCOMs, the title “senior enlisted advisor” [SEA] was adopted. I didn’t like the title at all, because I felt it as an effort to make the top chief on the base kinder and gentler. Indeed, SEAs were becoming more approachable and their role was expanding. The Air Force was coming to grips with a lot of social issues that included improving race relations, addressing the increased drug use among Airmen, and the rapidly expanding role of women in the Air Force. The SEA was now in a private office down the hall away from the command section. To me, there was some loss of daily access to the commander.

Further, the SEA title was abused widely. I recall having junior officers introducing a young master sergeant or technical sergeant to me as their “senior enlisted advisor.” The Air Force Personnel Center ran a listing for me on one occasion, only to find we had some 30,000 senior enlisted advisors in the Air Force against a quota of roughly 3,000 authorizations.

I had long, long thought we needed to change the title. We had actually discussed some options during CMSAF Dave Campanale’s tenure. We had mixed opinions at the table among the MAJCOM senior enlisted advisors. Some thought it would be seen as self-serving. One very strong advocate who shared my opinion was CMSgt Wayne Norad, the SEA for Air Force Special Operations Command. Wayne had spent a lot of time in the joint world and recognized the necessity for members from all services to be able to easily recognize the top enlisted leader, especially in a combat scenario. He had actually developed a prototype of the rank, a CMSgt tab with a star in the open field of the stripe. It was the precursor to the actual CCM [command chief master sergeant] stripe of today.

We had another hurdle. Gen. Ron Fogleman had changed all of Gen. [Merrill A.] McPeak’s uniform changes that he implemented a few years prior. For instance, Gen. McPeak had removed the stars from general officer uniforms and put the rank on the sleeves of the dress uniform, similar to the Navy. There were other changes as well, and Gen. Fogleman reversed nearly all of them. He was tired of making uniform changes, and rightfully so. He had told the Air Force the uniform board was no longer in operation for a while. And so the command chief concept was tabled without action. Since Gen. Fogleman had hired me to be the Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force, I was not in a position to bring a uniform change forward.

Following Gen. Fogleman’s retirement, Gen. Mike Ryan (my boss in USAFE) became the Chief of Staff. I thought, “Aha, I think we may have a shot at changing this.” I asked Chief Marc Mazza, the Air Force Material Command [AFMC] senior enlisted advisor to develop a talking paper and a prototype of the new stripe. I sat down with all of the MAJCOM SEAs [now known as the Enlisted Board of Directors, or EBOD] one last time and told them I planned on presenting the proposal to Gen. Ryan. I fully expected him to have me run it around the Air Staff for consideration.

It was a Thursday afternoon, and I went to see Gen. Ryan at his office in the Pentagon. We had both been traveling a lot, and so, it was time to catch up on a stack of issues and paperwork. We finally finished, and I said, “I have one last thing for you to consider. I put the talker and the visual representation of the stripe in front of him.” He looked it over and finally said, “I like it! Take it to Corona next week, and I’ll put it in front all the other four stars during our executive session.”

I was very excited that he had made his decision so quickly, and at the same time I knew I was behind the power curve. I didn’t have time to vet the concept through the former Chief Master Sergeants of the Air Force. This would not make them happy, and I knew that. I would have to take a lot of lumps from them. I immediately called all of the MAJCOM SEAs and told them to get with their four-star bosses to grease the skids before the executive session.

I had packages made for all the four stars. They went into private executive session for a couple of hours. When they emerged, Gen. Ryan handed me the packages and said, “Chief, done deal. Make it happen. They love the idea.”

I had a rocky relationship with the Air Force Times. It seemed the more I tried to be open and generous with my time with them, the more they screwed up what I said. The relationship had soured to the point where I requested the editor to come to my office for a discussion. I told him to have his reporters simply print exactly what I said—their embellishments were skewing my messages to our Airmen and forcing me to constantly correct what they had messed up. He finally acknowledged to me that if the Air Force Times did not print “edgy” material, Airmen would not buy the paper.

I wasn’t going to give them the opportunity this time. So, I called one of their reporters whom I trusted, a former Army sergeant public affairs–type, and told him, “I’ve got a story for you and will be faxing a photo shortly. I am asking that you print the story exactly as I am sending it—nothing more and nothing less.” He promised he would, and he did.

I did my best to prep the field for the announcement and used every public affairs option open to me. Of course, I did get some pushback from some chiefs—they felt somehow emasculated because one chief would have a stripe different than their own. I got numerous e-mails from disgruntled chiefs, and I responded to each of them with my rationale for making the change. I responded to each one appropriately.

But here’s the point. The concept is compatible with what we do with first sergeants. We put a diamond in their sleeve so everyone knows who they are. There are certain expectations when you see the diamond. That first sergeant represents the policies of the commander, discipline within the unit, responsibility for the health and welfare of his/her unit. They are also the standard bearer for their unit—hopefully holding everyone to a higher standard.

The command chief does a similar thing—they represent the policies of the commander and are responsible for the health and welfare of the unit. They also oversee the first sergeant community at their installation.

And we needed relevancy in the joint world. While in Bosnia, I would sometimes travel with the 1st Armored Division command sergeant major. He had a distinctive chevron, which made him stand out to his soldiers. I would walk alongside two other chiefs—no one knew who I was because our chevrons were the same. They didn’t know I was the USAFE senior enlisted advisor. When you walk into a room and there are 30 chiefs in there, one of them is the command chief. Our Airmen need to know who that person is.

The four stars loved it, every one of them, unanimous. They said, “Chief, if I wanted advice, I’d get advice. I need a ‘Chief’ who represents my command.” It’s another one of those culture things. I thought it was a great improvement, and I think it has served us very well since.

Today command chiefs are well known and well visible as the leaders of the enlisted force. As you were saying, anybody can identify them on the base. If you could give a bit of advice to senior NCOs or chiefs today, what would that advice be?