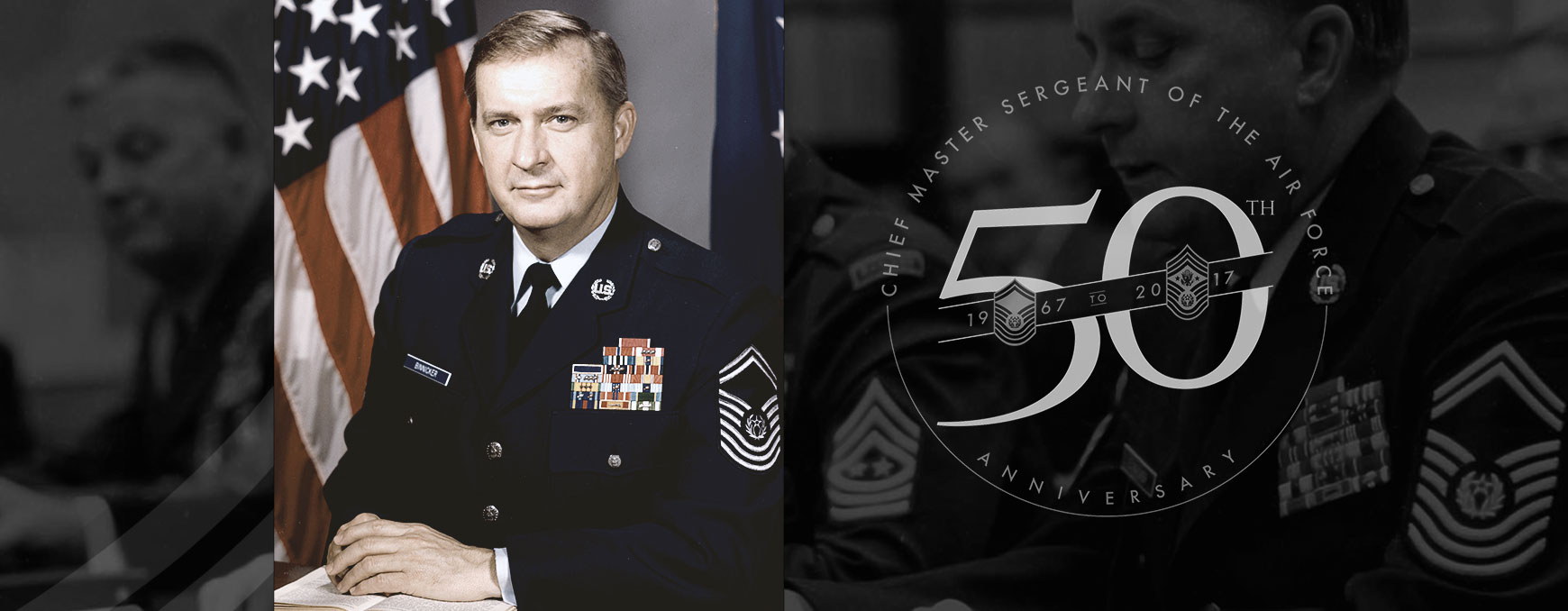

CMSAF James C. Binnicker

James C. Binnicker always wanted to fly. Born on 23 July 1938 and raised in Aiken, South Carolina, by his freshman year of high school he was a member of the local Civil Air Patrol squadron. He loved the camaraderie and the structure, the discipline and the flying. “I found that I was very comfortable and enjoyed putting on the uniform and dressing up like an Airman,” Binnicker recalled. “The marching, the flying, the saluting, that was sort of my thing; I liked it. And then when we went to summer camp, the exposure to...the real Air Force...solidified that this was what I wanted to do.”

In 1956 Binnicker was named Cadet of the Year and was awarded a scholarship to attend flight school. He also represented South Carolina in Great Britain as a foreign exchange cadet. By all accounts he was a successful cadet with a bright future in aviation. But a year later, in 1957, his path took an unexpected turn.

Binnicker signed up for the Air Force’s aviation cadet program with every intention of becoming a successful Air Force pilot, but doctors soon detected a high-frequency hearing loss in his right ear. He was disqualified from the program and returned home. Brokenhearted but determined to serve despite the limitation, he decided to enlist. As he recalled after a long, successful Air Force career, “I was disappointed and didn’t want to go back home and face the people I had sort of thumbed my nose at—’I’m going to go off and be jet pilot’—so I told the recruiter I wanted to join the Air Force.”

The hearing loss disqualified Binnicker from several jobs, but he found a career field that allowed him to serve close to airplanes and pilots: personal equipment. He spent the next few years at Altus AFB, Oklahoma, installing parachutes and other survival equipment in B-52 Stratofortress long-range bombers and KC-135 Stratotanker aerial refueling aircraft.

He quickly grew accustomed to the Air Force culture in the late fifties. He joined the Aero Club, went to movies with friends, and hung out in the barracks dayroom. He learned the benefit of mentorship from his experience with a maintenance chief, CMSgt Roy Duhamel, and grew frustrated with the barracks set up of two Airmen to a room and a shared bath, which was the norm until the late nineties, well after he retired.

His career took off as his supervisors recognized his motivation and natural ability to lead. He cross-trained into the air operations career field in 1964 and moved to Hickam AFB, Hawaii, as a staff sergeant. While there, he planned flights going into Vietnam and quickly made technical sergeant. Over the next 10 years, he served in North Dakota, Vietnam, Georgia, Taiwan, North Carolina, and Texas.

In 1977, now a chief master sergeant and experienced senior enlisted leader, Binnicker began serving in a unique role. Pres. Jimmy Carter established a commission on military compensation with the specific charge to “identify, study, and make recommendations on critical military compensation issues.” With Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force (CMSAF) Thomas Barnes’s recommendation, Binnicker became the senior enlisted adviser on the commission.

The members researched and made recommendations on different forms of compensation, including basic pay and allowances, special and incentive pays, and retirement benefits. It was one of many experiences that prepared Binnicker to later serve as the CMSAF, and he credits Barnes for his success. “He involved me in some things that gave me visibility that I might not have gotten otherwise,” Binnicker said. “I kind of point to him as the guy [who] had the most influence and impact on my career.”

Following his yearlong assignment to the compensation commission, Binnicker returned to serving as a senior enlisted advisor for the 12th Air Force at Bergstrom AFB, Texas, and later for the Pacific Air Forces Command at Hickam AFB, Hawaii. He was then selected to serve as the chief of the Chief’s Group at Randolph AFB, Texas, before serving again as a senior enlisted advisor, this time for Tactical Air Command.

In 1986 Gen Larry Welch, selected Binnicker to serve as the 9th Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force. He quickly adapted to working on the Air Staff and began to implement a variety of initiatives, most notably a new Enlisted Evaluation System that introduced the Performance Feedback Worksheet and the Enlisted Performance Report. He also began to enroll master sergeants into the Senior Noncommissioned Officer Academy and led through a significant drawdown of military personnel that impacted promotions and disrupted the force. When he became the CMSAF in 1986, the Air Force had 603,714 Airmen on active duty, but by 1990 that number had dropped to 535,233.

Binnicker retired in 1990, but he continued to serve in a variety of Air Force roles. He was a member of the Air University Board of Visitors and the Airmen Memorial Museum. He traveled around the world to speak to Airmen in different forums including professional military education (PME) courses. In 2000 Binnicker became the chief executive officer of the Air Force Enlisted Village, where he worked tirelessly to create a safe and loving home for more than 400 residents. Binnicker passed away from cancer on 21 March 2015.

Before his passing, Binnicker did not sit down for a long-form oral history interview. However, as he often said, he never met a microphone he didn’t like. The following are quotes and perspectives that Binnicker shared throughout his life and Air Force career.

On the promotion slowdown in 1987:

“The no. 1 issue, no. 1 concern, no. 1 problem in the Air Force today is the promotion situation. Not only from those people who are holding a line number, but those people who hope to get promoted, and even those people like chief master sergeants who can’t get promoted but are concerned for their people."

“I just don’t think that a lot of people understand the ramifications of our promotion system. That is, we are restricted as to how many people we can have in each pay grade and we historically have promoted to the maximum in each pay grade.”

“When FY [fiscal year] 87 promotion time came we did not have approval authority for the remaining increases but we felt they would be approved. It was a gamble, and we lost. I know a lot of people find it hard to believe, but the promotion delay was not caused by budget cuts, I can assure you that is true."

“The good news is we’re confident that we’ll be out of this delayed promotion situation by the end of December. We’ll be back on track, however, I predict the numbers will be smaller in future promotion cycles for the next couple of years due to continued good retention and reduction in force size.”

“I remember in the 1950s when promotions were frozen. That meant there weren’t any promotions at all. So, the possibility is there. The percentages are small, but at least we can look up and see that there will be some stripes forthcoming. Given that information, the idea is to be competitive and go for it."

“Some people will rationalize that, well, if I had been given a medal from my last unit I would have been competitive. That is rationalization. They should never use that, as far as I’m concerned. If they had studied harder and made five more points on their score, the medal would be a moot point.”

On involuntary overseas extensions:

“I went to Germany just before the changes were announced. Though there was uncertainty, moral was high. Then, after the tour extensions were announced, I visited nearly every Air Force unit in England. Most people I talked with wanted to stay in Europe longer. The Air Force did a good job handling a potentially demoralizing situation by keeping everyone informed why these changes were necessary."

“Many weren’t [happy]. That was a difficult decision, but we’re doing all we can to end the program. Given the time and budget constraints, we had to decide how best to cut PCS [permanent change of station] costs quickly. Now we are exploring additional ways to cut moving costs. We can probably save money moving people to a base nearer their current assignment, if there is a vacancy or requirement. That doesn’t mean everyone returning from Europe will go to an East Coast base just because it’s cheaper. Mission requirements still come first."

On issues that threatened recruiting and retention during his tenure:

“Smaller pay raises, for one thing. Plus, the perception blue-suiters are losing benefits. It reminds me of the talk in the ‘70s about an ‘erosion of benefits.’ We weren’t losing a lot of benefits, just perceiving a loss."

“We need to inform people about what is happening to benefits. Then, when they read rumors about benefits in a local newspaper, they might not jump to conclusions or make a rash decision to leave the Air Force."

“[Benefits] are important, but satisfaction is a more important motive to stay on. Satisfaction with where you are, who you work for and, especially, how you’re treated. When you go to the personnel or finance office, do you get prompt, efficient service? We’ve got the best medicine in the world and top-notch doctors, but sometimes, in some places, getting an appointment is major problem. We’ve got to become more efficient at providing these services.”

“People very quickly could fall into the mode of not caring if people want to stay in. We have to care. The plan is to keep the very best people. A good way to do that is to provide them a lifestyle that makes it comfortable for them to stay. Then we can make great demands on them. We can have high standards and work them very hard. Because when the smoke clears, we’re still going to have an Air Force.”

On changes to enlisted professional military education during his tenure:

“We’re putting the M back into PME by shifting to a more practical curriculum. We’re reducing the time spent in world affairs and devoting more to NCO subjects—things NCOs need to do their jobs—and writing exercises that relate to the job such as performance reports, staff summaries, and talking papers. We’re not eliminating world affairs; since we make PME-completion a major factor for promotion, shouldn’t we then ensure that the curriculum closely relates to supervision and management?”

On the transition from the Airman Performance Report (APR) to the Enlisted Performance Report (EPR) and Performance Feedback Worksheet:

“[APRs] had become, in my opinion, a meaningless document because 98 percent of the Air Force had the same...[rating]. I was never convinced—nor am I today—that 98 percent [of the force] is perfect; and essentially that’s what we were telling them, that 98 percent of the Air Force is perfect. And when you give everybody the same report card, then you hurt the people who are truly the exception. The old APR...was not a bad system. We had just abused it to the point [where] it was ineffective. If we had followed the regulation and treated it the way it was designed years ago, then it would have served us forever because it was well designed. It had just [come to the point where] if you [didn’t] get a nine, you were dead."

“Somehow we had come to think that if you didn’t get a report card all the way to the right, there was something wrong. I was just hoping that, over time, we would accept a report card that might not be all the way to the right."

“Feedback was something I thought was absolutely essential—still do. It wasn’t done very well in the beginning, but I saw it as a tool to help supervisors in many ways. You’ve told them up front what your standards are; at midpoint you said, ‘this is how well you’re doing’—or not doing—and then the report card.”

“We needed to [make some changes] quickly, before we got too far into the evaluation system. If we had waited too long, there would have been more reports rendered, and we would have had to have gone back and possibly redo those. So we just felt that if we’re going to do something, now is the time to do it. And it was done very quickly. We had a gut feeling—from conversations with senior NCOs and commanders that this thing was not as smooth as we thought it might have been.”

“When we first started last May, our education program was not as comprehensive as I would have liked. Some people did a superb job. Those who didn’t were the root cause for a lot of misconceptions, myths, and just plain misunderstanding around the Air Force-it was a reflection of the quality of the education program."

“We’re going to put additional emphasis on educating everyone, including senior raters, officers, supervisors, civilian supervisors—anyone who’s in that process should be educated and told how to render a report under the new Enlisted Evaluation System."

“We should completely forget the APR philosophy. We need to take this new evaluation system and rate people based on their performance today not try to conjure up some kind of equalization table that says a ‘7’ [APR] is equal to a ‘3’ [EPR] because it’s not. If I give a master sergeant a ‘3’ under the new system, I’m going to slow him down. He won’t get promoted as fast, but I’m saying he’s a satisfactory performer and should be considered for promotion. Will he be promoted? That depends on his whole record.”

“It will take a while for people to get used to it, understand it, and accept it. Some people will never accept it. They’ll just have to leave - so we’ll do that through attrition.”

On his experience working as the chief of the Chief’s Group:

“I, like a lot of people in the Air Force, had some preconceived notions about personnel; I think personnel gets a bad rap because of the business that they’re in. They’re either moving you or promoting you or educating you, and those are things that are near and dear to everyone’s heart. So if you can’t satisfy everyone, obviously you’re going to have a bad reputation. The training, the exposure I got while working at the Chiefs’ Group, I think, [enabled me to] go out and defend the personnel system. When you’re standing on stage and someone is upset with the personnel system—either they didn’t get promoted or they didn’t get the assignment they wanted—it certainly helps...to be able to...explain the system...from the standpoint of having worked there and understanding the system.”

On master sergeants attending the Senior NCO Academy:

“When I was a chief-selectee, I felt cheated because I had a strong need for [the information gained at the academy] a lot earlier. And I felt that the payback would be greater [if] we would expose master sergeants to this information. That’s the beginning of the senior NCO corps. We call master sergeants senior NCOs; we include them in the Top 3; we call it the Senior NCO Academy, yet we don’t send them to the senior school. The primary purpose would be to send the master sergeants earlier to take advantage of this newfound knowledge, and they would be better prepared, I think, to move into the senior and chief ranks, and take those positions of greater responsibility.”

On the future role of women in the military and the potential for a female Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force:

“[In the past], female members would get promoted up to a particular grade—usually a master sergeant or senior master sergeant—and then get frustrated with the system because they could see that they are not going to get the choice positions that other chiefs might get. [Today], young women at the staff or tech sergeant level [can] see that ‘Hey, there is a reason for me to stay in the Air Force.’ And they are obviously staying longer and doing quite well, I think, in being competitive for jobs. It’s just a matter of time before we have a very serious candidate for Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force who happens to be a woman.”

On the mission of the Air Force Enlisted Village:

“Our mission at the village is simply to provide a home. It started out with only Air Force enlisted widows, but over the years we have changed that to include a lot of different kinds of people. We take care of Air Force enlisted widows first and foremost, that’s the priority. Then we have moral dependents, when it’s just the right thing to do."

“It’s not just a retirement home for widows. It is a community. It’s an extension of the Air Force family, and we are very proud to provide that. The village is not a place where people go to die; it’s a place where people go to live...We don’t just provide an apartment; it’s a way of life.”

On how he would like to be remembered:

“That I did my best. I would hope most people would say the same thing...and that’s all you can do. That’s all that the country can ask of you...that you do your best. That’s how I’d like to be remembered.”