A Brief History of the Enlisted Force

The Air Force may be the youngest of the US military services, but through the years, it has become the most capable and feared aerial force in the world. While Air Force officers have made significant contributions to this success, so too has the enlisted force. The Airmen who come to work with stripes on their sleeves have served as the backbone of the Air Force for several generations. Maintainers, cooks, security policemen, radio technicians, medical professionals, and many other enlisted Airmen have played a crucial role to accomplish the mission and keep aircraft flying, fighting, and winning in the skies above. Over the last 70 years, the enlisted force has evolved into the most educated, experienced, and professional force the world has ever seen by taking significant, purposeful strides within the realms of experience, professionalism, diversity, education, and training.

The Beginning

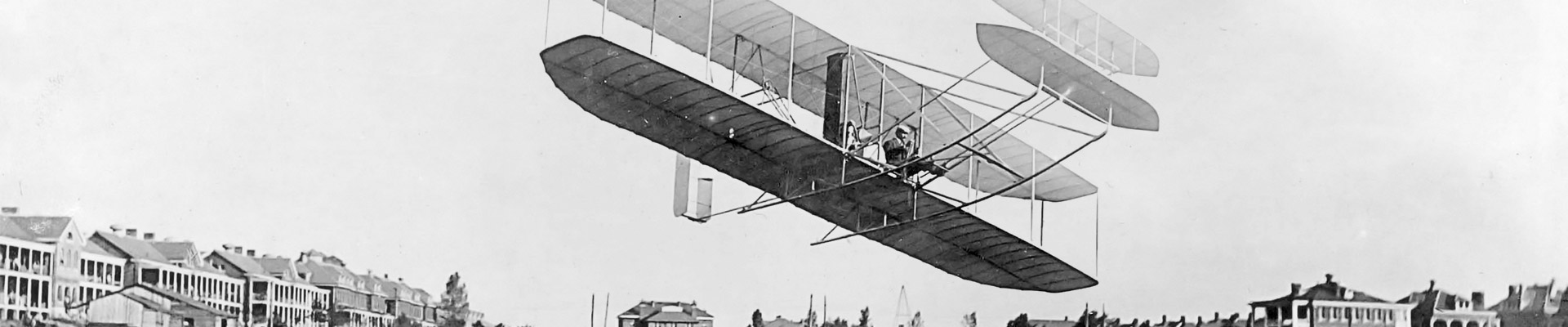

In 1907, just four years after Wilber and Orville Wright took flight at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, the US Air Force of today first established its military roots as the Aviation Section of the US Army Signal Corps. The division was created to take “charge of all matters pertaining to military ballooning, air machines, and all kindred subjects,” according to notations by the Air Force Historical Research Agency. The Aviation Section was built up during modern aviation’s early inception and initially only had stewardship over 10 hot air balloons. A year later, the Army began flight testing airplanes at Fort Myer, Virginia. One pilot, Lt. Thomas E. Selfridge, died in a plane crash during the testing stage, but the early aircraft, a Wright Model A, was improved upon. Subsequently, “Airplane No. 1” was adopted into the Army’s aerial arsenal on 2 August 1909.

The Aviation Section was initially authorized an enlisted force of just over 100 men. To work in the newly created job field, the Army desired that the service members—pulled from those already active in the service—gain a solid technical knowledge of the aircraft. By 1914 the Aviation Section had created a training structure for the enlisted members. In order to receive job certifications, the early “Airmen” required a degree of comprehensive testing and specialization; they had to show they were proficient in airframe maintenance and repair, as well as engine construction and maintenance. As an added incentive to complete the training, certification came with a specialty title of Air Mechanician and a 50-percent pay raise.

This upgrade process was in place until 1926. In Generations of Chevrons: A History of the USAF Enlisted Force, Janet Bednarek speculates that the timeframe between 1917 and 1942 represents one of the biggest jumps forward in early aviation technology. During an era of ever-growing aviation advancements, enlisted maintainers had to grasp the technical details of each type of aircraft: from the Curtiss JN-4D “Jenny” [1917], a wood and fabric biplane with a 90-hp OX engine, to the more complex Boeing B-29 Superfortress [1942], an all-metal long-range heavy bomber, sporting four 2,200-hp radical engines.

Testing the Battle Mettle of Early Aviation

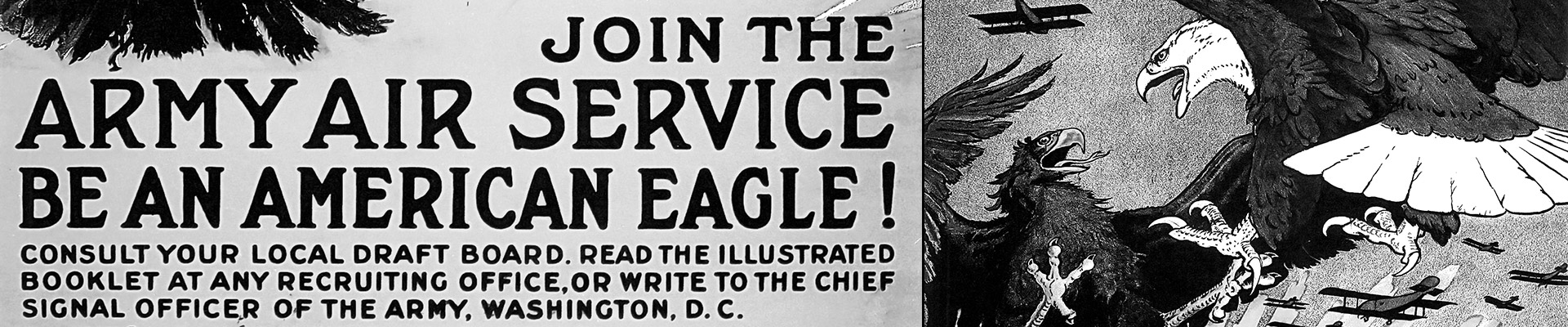

Ready to apply the aerial capabilities of its newest section, the Army wasted little time before sending aircraft on missions. As early as 1916, the 1st Aero Squadron—the first air combat unit of the US Army—was rallied to the skies to help in the search for Pancho Villa, a Mexican revolutionist who had led a raid in Columbus, New Mexico, killing 17 US citizens. This mission marked the first time the United States had ever placed a “tactical air unit” in the field. When the 1st Aero Squadron reached the Mexican border with eight JN-4Ds in tow, the unit was made up of 11 officers, 84 enlisted men, and one civilian mechanic. Although their pursuit of Villa was unsuccessful, the 1st Aero Squadron was able to gain “valuable field experience from operating under ‘combat’ conditions” while navigating over the mountainous terrain of northern Mexico. It was training they would tap into sooner, rather than later, when the United States declared war on Germany on 6 April 1917. Leaving New Mexico behind, the unit traveled to France and became the first US squadron to enter World War I. The squadron’s original role was that of an observation unit, initially flying a two-seater recon plane—the French Dorand AR.1 and AR.2. By then, the US Army Aviation Section consisted of 131 officers, 1,087 enlisted men, and fewer than 250 airplanes. Twenty-four squadrons had been added to the aviation arsenal by early 1917; however, only the 1st Aero Squadron was fully equipped, manned, and organized by the time of America’s declaration of war.

Enlisted mechanics became a valued commodity in the Aviation Section, but it wasn’t the only job offered to enlisted Airmen in the early days of the Air Force. Other career choices were available, including photo reconnaissance and radio. Within a year of its activation in Germany, the Aviation Section began to set up technical schools and institutions for enlisted members to develop their technical skills. As noted in the Airman Handbook, two of the largest schools were in St. Paul, Minnesota, and Kelly Field, Texas. Later, mechanics and other enlisted specialists received more training while deployed to the fields and factories of Great Britain and France.

The Army’s aviation branch changed in name and structure over the next 30 years as it continued to grow into its own distinct organization. Toward the end of World War I, the Aviation Section was redesignated as the Air Service via an executive order given by President Woodrow Wilson on 20 May 1918. In its few months of combat action, the newly established Air Service conducted 150 separate bombing attacks, dropping roughly 138 tons of ordnance—some as far as 160 miles behind enemy lines in Germany. All told, the Air Service downed 756 enemy aircraft and 76 enemy balloons, while losing 289 airplanes and 48 balloons from the United States.

Military aviation and the enlisted force continued to evolve. On 2 July 1926, the Army unit was once again redesignated, this time as the Army Air Corps; it was redesignated again in 1941 as the Army Air Forces. Throughout this era of constant change, enlisted Airmen became more specialized. By the 1930s, the Army Air Corps had organized all of the force’s enlisted specialty codes to fit within 12 categories: airplane and engine mechanics, aircraft radio mechanics and operators, aircraft instrument mechanics, clerks, stewards and cooks, aircraft metal workers, aircraft armorers, meteorologists, parachute riggers, auto mechanics, aircraft machinists, and aircraft photo technicians. The Army Air Forces expanded upon this structure by adapting a more detailed training regimen that enhanced specialization. In Foundations of the Force, Mark Grandstaff gives an example by describing the classification scheme for mechanics, which included eight functional groups and 47 subclassifications. The Army also created new jobs in the areas of electronics, radar, and medicine. Enlisted members assumed more responsibilities; a few even crossed into careers mainly dominated by officers.

Though low in numbers, enlisted Airmen have served in unique positions throughout the history of aviation, to include brief stints as pilots. When the Air Force split from the Army in 1947 and became its own distinctive service, two enlisted pilots—Master Sgts. Tom Rafferty and George Holmes—remained on active duty. Throughout the service’s history, the employment of enlisted pilots has been debated several times. In Generations of Chevrons, Bednarek states that ultimately “the Air Service, the Army Air Corps, the Army Air Forces, and the U.S. Air Force retained the elite vision of pilots that precluded the otherwise qualified enlisted members from finding a permanent role as enlisted pilots.” The idea remained relatively untouched until 2015, when the Air Force announced a differentiation from that standard by outlining an initiative to integrate enlisted remotely piloted aircraft pilots into the intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance mission. In a 17 December 2015 press release, Secretary of the Air Force Deborah Lee James discussed the decision to accept enlisted pilots into the RQ-4 Global Hawk community:

Our enlisted force is the best in the world and I am completely confident they will be able to do the job and do it well. The RPA [remotely piloted aircraft] enterprise is doing incredibly important work and this is the right decision to ensure the Air Force is positioned to support the future threat environment. Emerging requirements and combatant commander demands will only increase; therefore, we will position the service to provide warfighters and our nation the capability they deserve today and in the future. This action will make the most of the capabilities of our superb enlisted force in order to increase agility in addressing the ISR needs of the warfighter. Just as we integrated officer and enlisted crew positions in the space mission set, we will deliberately integrate enlisted pilots into the Global Hawk ISR community.

A Separate Service

On 18 September 1947, the Air Force officially became an independent branch of the US military after the National Security Act of 1947 became law. Once separated from the Army and considered a coequal branch, the new service began to adopt its own set of regulations, customs, and training requirements, creating their own individual structure and eventually a unique heritage of aviation excellence.

Due to the Army Air Forces’s heavy involvement in World War II, much of the early structure had already been established at the time of the service’s independence. According to the Air Force Historical Research Agency: “Before 1939 the Army’s air arm was a fledgling organization; by the end of the war the Army Air Forces had become a major military organization comprised of many air forces, commands, divisions, wings, groups, and squadrons, plus an assortment of other organizations.”

For the first decade, the Air Force fundamentally remained much the same as it had been prior to 1947, with the exception of a few notable changes. In 1950 Gen. Hoyt S. Vandenberg, the second Chief of Staff of the Air Force (CSAF), officially introduced a new term, Airman, to distinguish Air Force enlisted personnel from the Soldiers, Marines, and Sailors of other services. Playing upon this term two years later, the Air Force made another change, this time to their rank system. Initially, the Air Force had carried over and used the Army’s enlisted rank structure, but in 1952 it changed the lower four ranks from Soldier designations like “private” and “corporal” to more aviation-centric terms: (starting with E-1) airman basic; airman third class; airman second class; and airman first class. The rank structure continued to evolve as the Air Force progressed. The young services’ technical expertise also began to grow, both in training and in career options. As the Air Force diversified its combat capabilities over the decades, more career opportunities were created—by 2015, the number of available enlisted Air Force specialty codes surpassed 130.

The Air Force continued to distance itself from the Army in 1959 when it discontinued the warrant officer program. Since becoming a separate service, the Air Force had struggled to find a place for warrant officers. Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force (CMSAF) Donald Harlow once commented that warrant officers were “neither fish nor fowl.” According to Air Force Regulation 36-72, Officer Personnel, 2 June 1953, warrant officers filled superintendent Air Force Specialty Codes and positions that required qualifications beyond those of master sergeants. However, warrant officers were often not available to fill the superintendent positions, and master sergeants assumed the duties.

A year earlier, in 1958, Congress had granted the Air Force permission to establish two new enlisted grades: E-8 and E-9. Prior to the change, the highest rank an enlisted Airman could attain was an E-7 master sergeant. This led to an abundance of E-7s; master sergeants often supervised master sergeants who supervised master sergeants. By approving the two new grades, Congress hoped to delineate responsibilities in the enlisted structure and resolve enlisted retention issues due to a lack of promotion opportunities. On 1 September 1958, 2,000 Airmen were promoted to senior master sergeant, and the first chief master sergeants were promoted from that group the following year.

The two new grades led the Air Force to reconsider the warrant officer position. The Vice Chief of Staff of the Air Force, Gen. Curtis LeMay, initiated a review of the position by forming an ad hoc committee in 1958. The committee determined that warrant officers amounted to an added layer of supervision between officers and noncommissioned officers (NCO) that was unnecessary for mission accomplishment, and that using E-8s and E-9s to fill superintendent positions was significantly less expensive than using warrant officers to perform similar duties. The following year General LeMay approved the recommendation and officially announced the decision to discontinue the warrant officer program.

The creation of the senior and chief master sergeant ranks also marked the very beginning of the transition to a professional enlisted force. Senior NCOs assumed leadership positions and began to focus on leadership skills. Although the transition to a professional force would slowly progress over time, the first CMSAF commented that the transition can be traced back to a greater focus on leadership: “In the late 1950s, we started the United States Air Force as we know it today. We started to lead people, not drive them, and it was a decided change that slowly but surely evolved.”

As the Air Force continued to evolve during its first two decades as a separate service, the recruitment and retention of highly skilled enlisted Airmen became a priority. Air Force leaders began to focus on quality-of-life issues and ways to make a career and benefits in the military comparable to those in the civilian sector. Leadership began to address several key issues, such as competitive pay, retirement options, medical care, and housing. As Bednarek points out in Generations of Chevrons, “At points, progress would be made. But then larger forces—the Vietnam War, inflation, fluctuating defense budgets—often contributed to a renewed decline in conditions.”

The elimination of the selective service draft and the introduction of the all-volunteer force in 1973 put quality of life issues back at the forefront. It also had arguably the greatest impact on the quality and professionalism of enlisted Airmen. Although the Air Force did not have to draft enlisted Airmen, many of its members had joined the Air Force to avoid joining the other services. According to CMSAF Eric Benken, the transition to the all-volunteer force was “when we started . . . the beginnings of all of the talk about the professional force we have today. Because now you have people who are volunteers. So now first sergeants don’t have to focus every day on the discipline issues. They don’t have to focus on kicking people out of the service and all that. Now they can focus on quality of life.”

In the 40-plus years since the all-volunteer force became a reality, enlisted Airmen have developed into the most professional NCO corps around the world. There are many reasons for the professional development, including the implementation and evolution of the Weighted Airman Promotion System, Enlisted Professional Military Education, the Community College of the Air Force, and the Enlisted Evaluation System.

The Diverse Makeup of the U.S. Air Force

Modern diversity within the Air Force, still a work in progress, has come a long way since the branches’ earliest inception. To get to where it is today, the service had to first overcome many barriers, especially concerning the integration and equal treatment of African-Americans and overall inclusion of women in the Air Force.

The Tuskegee Airmen, decorated African–American pilots from the Army Air Forces, are famous for breaking down many of the racial barriers experienced by black people in the military. At the time, African-American’s were segregated into their own squadrons. Treated differently, they did not receive many of the same career opportunities and resources awarded to other ethnic groups. The contributions of the Tuskegee Airmen were further compounded by other enlisted African–American Airmen, who during their early history in the service demonstrated that skin color had nothing to do with proving a person’s capabilities.

As a move to cut down on intolerant practices within the US military, Pres. Harry S. Truman signed Executive Order 9981 on 26 July 1948. Under the order, Truman declared that, from then on out, there would be “equal treatment and opportunity for all persons in the armed services without regard to race, color, religion or national origin.”

A few months earlier, the Air Force had begun to study the impact of segregation on its ability to accomplish the mission effectively. Lt. Gen. Idwal H. Edwards, Air Force Deputy Chief of Staff for Personnel, directed Lt Col Jack Marr, a staff officer in the office of Air Force personnel, to study the issue. In the end, the study found waste and inefficiency in only employing African-Americans in certain capacities.

The study influenced Gen. Carl A. Spaatz, the first CSAF, to issue a statement on integration in April 1948. Spaatz promised that Air Force African-Americans would soon be “used on a broader professional scale than has obtained heretofore.” He stated that all Airmen would be guaranteed equal opportunity regardless of race and that “the ultimate Air Force objective must be to eliminate segregation among its personnel by the unrestricted use of Negro personnel in free competition for any duty within the Air Force for which they may qualify.”

A year later, on 11 May 1949, the Air Force officially released letter No. 35-3 stating, “There shall be equality of treatment and opportunity in the Air Force without regard to race, color, religion or national origin.” Integration of units began immediately, and on 1 June 1949, Air Force basic training officially ended racial segregation, assigning recruits to squadrons by gender and time of arrival only.

Thomas N. Barnes joined the Air Force in 1949 and was in one of the last segregated flights of basic training. He became an aircraft maintainer specializing in hydraulics and was the first African-American in his unit. Twenty-four years later, he became the fourth enlisted member appointed as the CMSAF and the first African-American to hold the position. While in office from 1973–77, Barnes made many notable contributions to the evolution of the enlisted force, but in many ways he is known for his greatest passion: working to ensure equality among the great Airmen comprising the US Air Force. One of the most common questions Barnes heard during his early tenure was, “What programs will you implement for blacks?” To which he recalled replying, “None. I told them I worked for all blue suiters.”

Barnes was anything but alone in his conviction for an inclusive Air Force. In the 1970s and 1980s, the Air Force was still combatting echoes of racial discrimination but also began to purposefully move toward gender equality. In 1948, the Women’s Armed Service Act of 1948 allowed women to lawfully serve in the armed forces, but they could only make up two percent of the service and only could serve in a handful of jobs. In 1967, when Paul Airey was appointed the first CMSAF, there were only 5,000 authorized enlisted women positions in the Air Force.

As time progressed, women were given more career opportunities, and their numbers rose to 10 percent of the force by 1979. Still, there was more to be done to fully integrate women into the service.

For the most part, this was supported by the Air Force’s highest enlisted leadership. CMSAF Robert Gaylor was one of the many supportive voices:

People should have the opportunity to do that for which they have been trained and prepared, and which fits their desires....I think we just have to ensure our people are given an opportunity. If they can’t cut it, regardless of race, creed, color or sex then someone else should be in there, but they should be given a chance to show whether they can do it or cannot do it.

In the past decade, the Air Force—along with the entire Department of Defense—has gone to great lengths to make sure service members from all backgrounds and demographics feel included and valued. Some of the biggest initiatives in recent years were the repeal of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” in September 2011, which allowed gay military members to serve openly in the armed forces. To better support military mothers, the Air Force extended maternity leave from six weeks to 12 weeks and extended deferments for deployment and physical fitness tests from six months after childbirth to 12. Another momentous change came on 3 December 2015, when Secretary of Defense Ash Carter announced that, beginning in 2016, all military occupations and positions would be opened to women. According to Secretary of the Air Force Deborah Lee James, this declaration opens up 4,000 jobs for females in the Air Force across six career fields.

According to James, progress has been made in this endeavor to welcome diversity, but “We (the Air Force) can do better,” she said. To cement their commitment to improving upon conditions for tomorrow’s Airmen, Air Force’s top leadership in 2015—CSAF Gen Mark A. Welsh III, CMSAF James A. Cody, and Secretary James—signed a memorandum on diversity and inclusion that read in part:

Across the force, diversity of background, experience, demographics, perspective, thought and even organization are essential to our ultimate success in an increasingly competitive and dynamic global environment. As airpower advocates, we must be culturally competent and operationally relevant to effectively accomplish our various missions. As Airmen, whether military or civilian, we must continue to build and maintain our commitment to diversity, inclusion and the associated promise of enhanced mission performance. These concepts infuse innovation and forward thinking into our culture and mission areas and resonate within our service’s core values demonstrating that integrity first, service before self, and excellence in all we do are part of our character.

Though it continues to be a young service, the Air Force and its enlisted Airmen have made a name for themselves over the years as an aerial force to be reckoned with. They are professional Airmen, committed to service in the profession of arms that requires a commitment to dignity and respect for all who choose to serve. Enlisted Airmen have evolved from the first mechanics working on the Wright Model A to today’s enlisted force made up of 395,000 professional Airmen in the active duty Air Force, Air National Guard, and Air Force Reserve.30 Each conflict or war entered into by US Airmen—from the first air missions in World War I through Vietnam, the Cold War, Operation Desert Storm, and up to today’s Global War on Terror—have provided the experience and knowledge to strengthen the force of the future. The combat experience of today’s enlisted Airmen, combined with their professional development gleaned through training and education, highlights just how far the enlisted force has evolved since its inception and just how far Airmen can carry the force into the future.