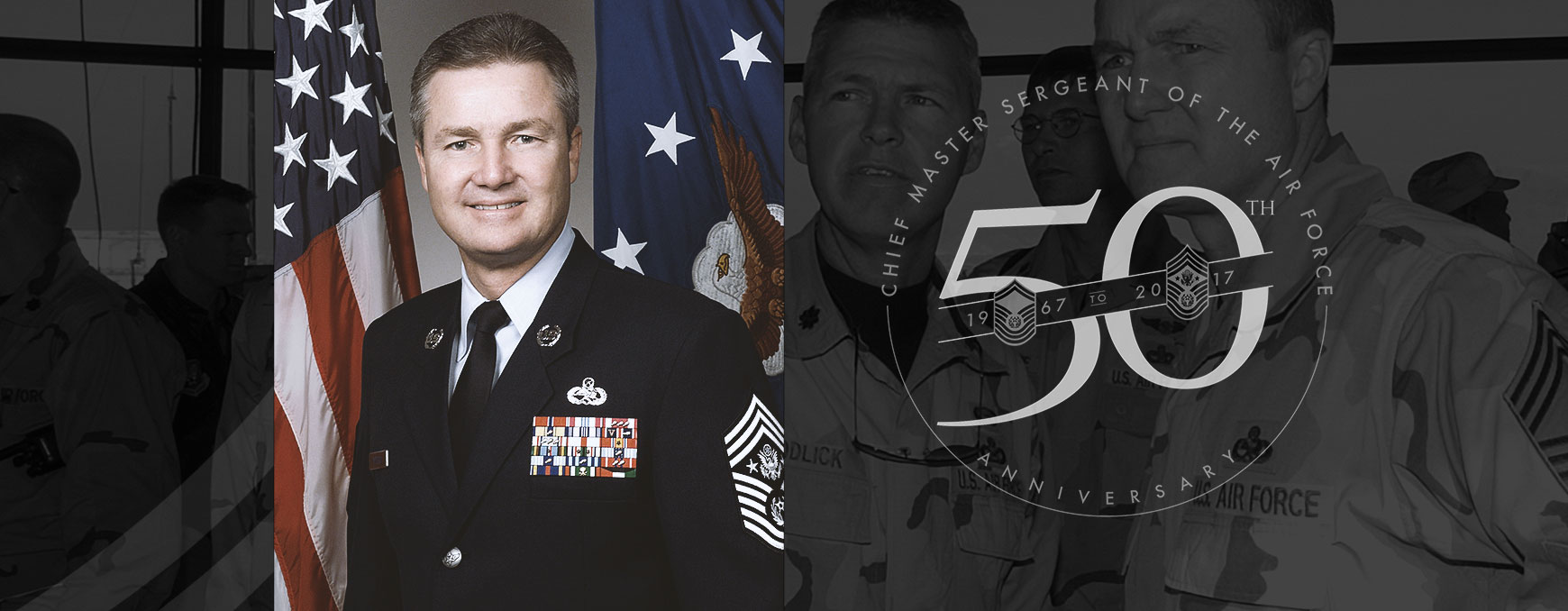

CMSAF Gerald R. Murray

Gerald Murray always knew that one day he may join the Air Force. His family has a long history of service going back to the Civil War, and jets fascinated him from an early age. In the late 1970s, when the economy fell flat and inflation was on the rise, Murray visited an Air Force recruiter with one simple request: make me a crew chief. The recruiter granted his wish, and in 1977, at age 21, he joined the Air Force.

Murray’s first assignment was to MacDill Air Force Base (AFB), Florida, where leadership quickly recognized his maintenance skills and work ethic. Three years later, he was selected to be a maintenance aircraft instructor and transitioned to Shaw AFB, South Carolina, where his career continued on a successful glide path. He was one of the first crew chiefs to work the transition from the F-4 to the F-16 aircraft, was one of the first Airmen deployed to Kuwait in support of Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm, and was selected to set up an A-10 squadron that broke records: meeting initial operational capability faster than any squadron since World War II, deploying, then setting some of the highest sortie production rates in the Air Force.

Gen. John P. Jumper selected Murray to be the 14th Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force (CMSAF) in July 2002, and Murray immediately focused on efforts to evolve the expeditionary air force to meet the challenges of a changed world following the terrorist attacks of 9/11. He reenergized the NCO Retraining Program to balance manpower across the force, introduced the Basic Expeditionary Airman Skills Training (BEAST) Week at Basic Military Training (BMT), and introduced a completely revamped physical fitness test—a move that strengthened the culture of fitness in the Air Force. Murray retired in June 2006 after 29 years of service.

In November 2015, Murray sat down for an interview to discuss his Air Force career and tenure as the CMSAF. During the interview, he talked about his passion for aircraft maintenance and the challenges of transiting to a newer-generation aircraft, his experience as one of the first on the ground in Saudi Arabia for Operations Desert Storm and Desert Shield, and his focus on pushing the Air Force expeditionary mind-set further. The following are edited experts from the conversation.

Well Chief, I really appreciate you taking a bit of your time to sit down for this interview.

No, no, thank you. I think it is so important because, you know, it’s hard to believe that 50 years ago now, coming up on it, that Chief Airey was our first Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force. I think it’s very important to document our history this way.

I agree. What we’d like do is go through your career and just have you offer your perspective on a few points you experienced. I know you joined the Air Force in the late 1970s…

1977.

Twenty-one years old, correct?

I was, yes.

That’s not uncommon for an Airman to join in their early twenties, but I’m curious to know if the Air Force was something you had already considered, and perhaps it just took a while to take the leap. Or was it a whimsical thought where you said, “You know, I’m going to go into the Air Force.” How did that play out for you?

Well, I have often told people that I joined the Air Force because I needed a job. There’s truth to that. I was working in home construction, building homes at the time, and the economy fell flat in the mid ’70s, and especially by ’77 the inflation rate was running very high. I worked for my father-in-law and with my brother-in-law. I really enjoyed it and thought that was where my career would continue, but the economy didn’t allow the start of another home. Unemployment was extremely high then, and so, I had to look at alternatives. I was married at the time, and so I looked at the service.

But now, back that up. There were preceding things that certainly led to thoughts of coming into the Air Force. I had two uncles that served in Vietnam—one drafted, one avoided the draft by volunteering to go to the Air Force. I had uncles that served in Korea, World War II, and World War I. My great-great grandfather actually died as a POW [prisoner of war] in the Civil War.

Those things from my family’s history, especially the two younger uncles, influenced me. And, oh by the way, I had to sign up for the draft during high school because Vietnam was going on when I was in school. So, those were some of the things and thoughts that pushed me to know that if I were to join the service, the Air Force would be where I wanted to go. And ultimately, I tell you, jets fascinated me. When I went to the recruiter I told him that if I come in the Air Force I want to work on fighter aircraft. I wanted to be a crew chief, and I got a guaranteed job with it. So, those were the things. But yes, it was a matter of, from an economic standpoint, the need for a job, but there was a history of influence toward service that led to my thoughts and actual decision to join the Air Force.

So it was probably quite an honor then to carry on that family tradition.

Yes.

What was your impression when you first joined and you went through basic training and got your first assignment? What was your first impression of Airmen and the Air Force culture?

Well, you know, a little of this comes in hindsight. I thought basic training was way too easy, you know. I grew up on the farm; I worked construction; I was really active in sports, and so, I was a little disappointed with basic training.

You roll that forward 25 years, those influences of basic training had a bearing on some of my decisions for the readiness of the force and things I put in place as Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force.

To simplify, basic training was too easy; technical school was too short. What used to be, in my maintenance career field, six months to nine months of tech school was cut to two months. So, it was way too short. The training and preparation to go do the job I felt was not adequate. And again, things were changed over time as well.

OJT [on-the-job training]...a lot of OJT, and of course that affected readiness. When I got to my first base at MacDill there were 96 F-4s. I will tell you, it was daunting to step out there, but it was exhilarating; it was exciting. We got our first duty station choice in Florida; so, we were pumped, coming out of North Carolina and we get to go to Florida. It was a very exciting time.

But the mixture of a lack of standards and discipline were challenging. Hair was a big thing, you know, long hair, drugs. There were inconsistencies I found in that timeframe. It was a very interesting view of the force, because a lot of things in society that were going on in the late ’70s were permeated in the Air Force as well.

What was interesting, though, was to start seeing that change. There were differences—both positive and negative. But it was an exciting timeframe out there on the flight line with a mission every day, with those jets flying, and being a part of that. That was exciting.

You mentioned you were down there, a crew chief at MacDill. Aircraft maintenance has always been a critical element of airpower and how we fight around the world, but as a young Airman sometimes, you don’t realize how important you are to that fight. Did that click for you pretty quickly?

I think it did. I was fortunate to have, I think, one of the best trainers, a young senior airman, Jeff Pellum, that set a great example about what it was to be a crew chief—the pride of the crew chief. Even back then, you longed to have your name on the side of that aircraft. When I got my name on the side, the pride I had in that, the ownership of that aircraft, was there.

So, from a maintenance standpoint, that was one of the important things: the symbolism that leads to ownership and a feeling that you are part of the mission. The other thing, I was recognized for my performance and selected as an instructor, which started broadening my aperture, even though it was still all focused on aircraft maintenance. This was something that evolved over time—to really see the impact and importance of your position in the Air Force. That of course then has to broaden out well beyond maintenance.

I was one of the first crew chiefs identified for [training on] the F-16, and I actually recovered the first F-16 block 25 aircraft that landed at Shaw AFB. Then I went into wing training to set up all the scheduling, and I was exposed to the National Guard. McEntire Air National Guard Base in South Carolina was the first guard unit to ever receive brand new aircraft, and I had a part in that. It began my education and understanding a little bit about the Total Force.

The other thing that really, I think, highlighted that view was attending the NCO Leadership School, which was a precursor to Airman Leadership School. Being exposed to multiple people from various AFSCs [Air Force Specialty Code], not just maintenance, gave me a greater appreciation of what we did as Airman and NCOs [noncommissioned officer].

Was there something there that made you decide, “Hey, I want to make this a career?” In the past, you’ve said you wanted to just do four years, but you obviously ended up staying longer than that. Was it that timeframe that did it for you?

It was. I actually reenlisted before going to Shaw because that was one of the requirements, but there were a few factors in that decision. A senior master sergeant by the name of Hillary McGartland—I called him Mac, he went on to be a great chief in our Air Force—he was from Shaw, came to MacDill, and started talking to me about the potential we might have from a cadre standpoint. He was just so impressive—I mean, he was super sharp; and so, ultimately, he had some influence.

I received a bonus, so money was a factor. I made staff sergeant under four years of service. So, I had line number for staff. They offered me a bonus. I sewed on staff, and got one and one-half times my pay to go with that.

I think the other factor in that was my leadership. The leadership support I had then, and the recognition—there was recognition of being an instructor, recognition of being one of the best maintainers. Then to be selected to cadre and the influence of a senior NCO [SNCO] there, that showed me the value of what I could do.

Then the assignment at Shaw Air Force Base was only two hours from where I grew up in North Carolina, and Sherry and I were ready to start a family. There are a lot of things that go through one’s mind; it’s not just one piece. But it was interesting how those things gave us what we needed to decide to reenlist.

It still was not, at that point, “I’m going to reenlist and spend 20–30 years in the service.” It’s an enlistment period, and ultimately, I’ve spoken—and have spoken for a long time—about a different way to get Airmen to look at their service. My desire is to do away with reenlistments for NCOs. I think our professionalism and where we are from a career standpoint lends to that. I’d like Airmen to take a little different view than I did. But again, those were factors that propelled me to a career.

Interesting. I think sometimes reenlistment as you get further along in your career becomes just a box you have to check because you know you want to keep serving.

Exactly, exactly. You know you roll that forward, when General [John P.] Jumper selected me as Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force, I’m thinking, “Wow this is great.” Then a personnelist comes to me and says, “Chief, you don’t have retainability.” I said, “What do you mean?” “Well, you need to reenlist because you don’t have the retainability to go take another assignment.” So, I go to my boss, General [William J.] Begert and I said, “Boss, can I stay in the service?” He said, “What are you talking about?” and I said, “I don’t have retainability for the assignment. I’ve got to reenlist.” (laughter)

So, we had fun with it, and actually I reenlisted in General Begert’s office, and we publicized it there in the paper in PACAF [Pacific Air Forces]. But again, why does someone selected as Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force have to sign another contract? Because at that time, you can’t run me out of the service.

That’s quite a story. Going back to the leadership you had in your early days as a maintainer, did they shape your leadership perspective and how you approached leadership for the rest of your career?

Absolutely. Like I said, having the great fortune to start out under a great trainer—Jeff went on to get his commission; he flew F-4s; retired as a lieutenant colonel—I had some great young leadership, and older leadership from that first base that had a good bearing on me. Then, of course, I talked about Chief McGartland at Shaw.

Along the way, too, I ran into some of the worst leadership I had ever experienced. In fact, a supervisor at Myrtle Beach [AFB, South Carolina], my first supervisor there, was probably the worst supervisor I have ever experienced in my life. So, I took lessons learned from that—this is the way you don’t want to be. Then the other thing is trying to, you know, understand and establish my leadership: how to train, how to supervise. But I was greatly influenced by those that I served under—both positive and negative.

Is it important for Airmen to start thinking about that early in their career?

It is. In fact, I spoke to an Airman Leadership School class the day before yesterday, and there is a standard question I love to ask all young Airman. I start out with, “How many of you have served under a bad supervisor?” It’s amazing to me—I say amazing, but it doesn’t surprise me anymore—that the vast majority, in such a short period of time, say they have. Then you peel that back. Why? Why is it—because we’ve put so much emphasis on leadership in the military—they believe they’ve experienced that? Have they really given thought as to why they would label someone a bad supervisor or leader, and then turn it on themselves? How do you think people speak about you? What would they say about you—good or bad? Why? Have you given thought?

So, I absolutely agree that the younger we can get people to think about their personal leadership and how they should be developing, the better. To get people to recognize, regardless if it’s a career in the military, it’s just life. As they’re going to develop in life, how are they developing? If they can put more deliberate thought to that, especially if they’re going to grow to be somebody who influences other people, is responsible for other people, and helps other people. I absolutely agree that we’d like them to think about that while they’re younger.

Yeah, that’s a good perspective. You talked about your experience early on transitioning to the F-16. I’m curious to understand some of the bigger challenges during that transition, because we’re going through a similar transition now with the F-35, as you’re very well aware.

Absolutely. You know, I work where I do today with fifth-generation type of aircraft, which are just incredible leaps in technology above the fourth generation. It was the same thing going from F-4s to F-16s.

The fundamentals of aircraft maintenance and aircraft systems is mechanical, hydraulic, and electrical, and that was what we basically were trained on and educated in. There were some electronics there, but not near what we adapted to in the F-16. Now I’ve got diagnostic systems in the aircraft and fault reporting with it. It was a totally different way to go about troubleshooting, to understand the aircraft. Then to go through the growing pains of this new technology that’s not completely perfected. To be able to go in and learn that, it was a huge jump for us from what we had started out in, basically, third-generation type aircraft. That’s the same thing I see going on in the force today. How do we help Airmen faster adapt to using this new technology today?

What I also find interesting, though, is in many cases young people today are very attuned to the information technologies, software, computing skills, and things of that nature. It’s interesting now to reverse it from our challenge. We were very adept to mechanical, electrical and hydraulics, and now we’re having to go back and teach some of those fundamentals.

Yes, it changes from generation to generation I suppose. Early in your career you were sent to Incirlik Air Base in Turkey. I’ve been there twice; it’s a great assignment. I know at the time, though, it wasn’t on the top of your list of places to go.

No, in fact, it was a complete surprise, no-notice assignment, to the point where I actually learned about the assignment by calling the [Air Force Personnel Center]. It took three weeks to get through the rotary dial system, the old dial telephones, just to have a senior master sergeant functional manager tell me on the phone that I had an assignment to Turkey. That was quite shocking to us.

We loved where we were at, the assignment at Shaw, what I was doing, and the job. I mean, things couldn’t have been better. And then, “We’re going where? Where is this?” We had to go get a map and find out where Adana, Turkey, was.

It was shocking to my wife, you know, the first time we had ever been out of the country, experienced anything like this, but it turned out to be one of the greatest things that ever happened to us. It opened our aperture to a world out there that we had never known growing up in the farmland in a small community in North Carolina. The mission I was exposed to—I was a crew chief on a Victor Alert pad, which was with nuclear weapons. Remember this was the Cold War era, so we actually kept aircraft cocked live with live nuclear ammunitions on them; so, an incredible mission.

And then the experiences of travel, interacting with the Turkish people and different people of all walks of life. The community ... you developed a sense of family, because you’re now thrust together overseas in a way, and you become much closer with your fellow Airmen and families. It really was a huge bearing on us. It gave us a sense that being part of the Air Force is also being part of a larger extended family. So, it was a great, positive influence for us.

What did it teach you about, you know, going places you didn’t necessarily want to go?

I think I got my choice of where I wanted to be assigned two times in the Air Force, and that was when I walked into the recruiter and told him I wanted to be a crew chief on fighter aircraft and at tech school when I got selected to go to MacDill, Florida. The rest of the time it was like, “I want to go here,” and “No, you’re going to go there.”

It put in my head what I’ve always used, which is remember this is an all-volunteer force. You volunteered to go to Korea; you volunteered to go to Turkey; you volunteered to go to Saudi Arabia, Iraq, and Kuwait. Whatever it is, you already volunteered for it when you came in and signed there.

The other thing it gave me, is to look at those things not as I didn’t volunteer for it, or as something I didn’t want to do, but ultimately, as an opportunity. Some of the greatest opportunities I had in the service are the things I never thought I actually would be assigned to do—either by job and position or my assignment.

Things you don’t necessarily want, then turn out to be...

Then turn out to be the best, yes.

That’s great. I wanted to ask you a question about the uniform, because I believe you were a master sergeant when we moved the master sergeant stripe from the bottom of the insignia to the top, is that right?

Actually I was a senior [master sergeant], and when it occurred I had actually sewn on chief. I was a senior master sergeant at McChord AFB, Washington, when Chief [CMSAF #10 Gary] Pfingston and General [Merrill] McPeak introduced the idea of the stripe, but it took time to get the stripes made and get them out. The sew-on date for that was 1 January 1995. Well, I sewed on chief on 1 November 1994; so actually, I take a little bit of pride that probably in history, I have worn more stripes as a chief than any chief ever will in the Air Force. I actually wore five different insignias as a chief master sergeant.

But, to what we thought about that, I tell you we looked at that as very positive. Throughout my career, it was always a big deal to become the senior NCO. From the time I was an airman basic, we emphasized our [AFI 36-2618] Enlisted Force Structure. The Enlisted Force Structure that was there in 1977 was put in place around 1972, but if you go back to senior and chief master sergeant, those two grades occurred in 1959. So, throughout history, we had the three tiers: your junior enlisted, your junior mid-tier NCO, and your senior NCOs—that top three. So, it was a big deal to become a master sergeant in the top three. I can tell that from the get go, the decision to take that stripe off and move it to the top was looked at as overwhelmingly very positive.

For me though, I said, “Well, it costs me money.” I had to buy those silver threaded stripes to go on my mess dress. I wore those on my mess dress for two months and then had to take them off, but we didn’t go back to the silver thread. We actually went to the regular stripes we have today. But, yes, I was a chief with two stripes above and actually became a chief with the three stripes above there in that transition.

You mentioned master sergeant has always been part of the top three in a three-tier structure, but was there a point maybe throughout your career where you started to see master sergeants taking on more of a senior NCO leadership role, or was it kind of always that way?

I think for the most part it was like that. I didn’t realize it when I first came in, but I saw a lot of junior NCOs—staff sergeants, tech sergeants—with some pretty key leadership roles, not knowing that after Vietnam they had drawn down the force in a way that stripped a lot of that mid-tier and master sergeants out. That changed after Desert Shield/Desert Storm when we actually took so many senior airmen to tech sergeants out that we had an overage of master sergeants.

But for the most part, in my career, we did recognize master sergeants as SNCOs. Of course by SNCOs, the master sergeants are the highest population. We saw that, primarily, our flight chiefs were master sergeants; so, we looked at that and expected that.

When I was at Myrtle Beach as a master sergeant production superintendent, my call sign on the radio was “Boss.” The master sergeant was the Boss, and I saw that throughout different career fields. That was always the crossover point, when the responsibility given there goes up. It still holds, and I think that it’s right where it is.

Interesting, thank you. You deployed to Saudi Arabia during the build up for Desert Shield, and you were there as Desert Storm kicked off, which has to be a fascinating part of history to witness. You were there at that moment, which was a huge turning point for our Air Force and for the military.

Right.

What was it like to be there at that time?

You know, right at first, it was a little scary there. We had spent my entire career at that point—13 years in the Air Force—in the Cold War, in garrison. A lot of deployments were small, short deployments that we would use for exercises to make sure we kept the force ready. I used to say, jokingly, that in the first 13 years of my Air Force career they sent me TDY [temporary duty] all the time, but my longest TDY was three weeks. And they sent me from Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, to Honolulu, Hawaii.

Desert Shield/Desert Storm changed all of that. It was about two weeks’ notice as we watched everything build up there after Iraq invaded Kuwait, and President (George H. W.) Bush made the decision and built the coalition that we were going to go do that.

So, I was on the first aircraft that landed there at the base we were going into. We, at the worker level, had little idea where we were at or what was going on. Was Iraq going to come on into Saudi Arabia? Was Saddam Hussein going to drive the Iraqi force into the kingdom? We didn’t know that. We had little protection around us; so, it was a little daunting with a lot of apprehension there. But once that did not occur, we built up our forces. You know, I have to go back. Where I came from, an A-10 base at Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, we could not have been any better prepared. I mean, we had peaked in preparation through ORIs [operational readiness inspection], OREs [operational readiness exercise], other types of training on how to mobilize, how to employ our forces. Then to be able to look at that awesome power—we had the ability to take and rapidly build up forces, bed down forces in preparation. It gave us a great deal of confidence that we were ready.

I believe, too, there was a mindset among us from the lessons of Vietnam. The leadership of our nation from the president, from the commander in chief down, had no doubt whatsoever that we were going to be victorious. We were going to take and execute a mission, and it showed in every sense. So, it was exciting and exhilarating. There was that sense of mission accomplishment that we took forward. And as we know, Desert Shield/Desert Storm was an incredible turning point in history. I think it was, in many ways, for the culture of our Air Force and who we are and what we do, and certainly our nation as well.

Was there any hunch then that 25 years later we were still going to be in the region?

No. I think looking back, it really is amazing to think about it. Everything we were doing was to execute a mission to be victorious. I would tell you, I think we questioned why our leadership pulled up and stopped. But then, when the president explained to us that the mission was to drive Iraq out of Kuwait, it was mission accomplished. So, we actually came home feeling good about that. We had accomplished that mission.

Now, roll that forward. I returned back again in 1995, and then I returned back again in 1997 under Operations Southern Watch and Northern Watch because Saddam Hussein didn’t learn his lesson—and this was after a massive drawdown of the force as well as a reorganization. We ended up having to deploy back into Kuwait, and we kept an established presence of aircraft and other forces there and in the Middle East through that time. That’s what drove us into having to go back again, because Hussein was threatening war in the region.

By then I was at Moody Air Force Base,[Georgia]; we were a lead air expeditionary force wing. We got the call, and with a 20-hour notice deployed the wing and established it. Of course, our ability to project power in such a rapid way was, I believe, the deterrent that kept Hussein from [invading] again.

But did we see this coming? No. Did we think we were going to be in a continuous war posture, if you will, for this number of years, since 1990? I don’t think anybody saw it coming.

You were there at the beginning, and of course you’re still involved with the Air Force and the military; so, I’m sure it’s a fascinating perspective looking back after all this time.

It is.

When you went out there the first time you were a senior NCO, up close leading Airmen. What inspired you about the Airmen you led at that time on the ground in the early 1990s?

I think, and again, I look at it from the perspective of the unit I was in and our readiness, we exercised and trained, and trained and trained; that was one of the big things about the Cold War that drove us. Although we were somewhat of an in-garrison force, we did deploy and exercise. I think it was a pinnacle of time for us in the force. After the drawdown of Vietnam, then over the course of the next decade an emphasis on rebuilding our military that came from the senior leadership of our nation. Of course, through the Reagan administration there was a commitment to the military—the funding we had, the new equipment we had. We were flying new F-16s and F-15s, and we had new technologies that were going into bear with us. We had robust education and training on the force. So, when we actually then had to commit it to a mission, the focus of the mission was just incredible.

The teamwork—I was amazed. My main base there in Saudi Arabia was King Fahd International Airport; that’s where we bedded down all the A-10s, special forces, our Combat Talon aircraft, and then a large part of the Army. From that main operating base, I was sent on Christmas Eve to King Khalid Military City, which is a northern Saudi Arabia base about 35 miles from the Iraqi border. It became the most-northern forward operating location. And again, from an A-10 perspective, that’s exactly how we had designed the A-10: to be close into the battlefront, turn back, rearm, refuel, and turn back to it.

We took people, if I remember correctly, from about 13 different bases, organizations, and units across the Air Force and brought them together there—people that had never worked together before. We’re not talking about one organization, one wing, squadron, or group. We cobbled this thing together from people that came from all of these, from European bases and different stateside bases and all different AFSCs. We put them together, and, again, our training was so well that we were able to establish that into probably one of the greatest units I’ve ever seen. So, the unity, the teamwork, and all of that came because we were trained in our jobs and we knew how to do it. We put together an organization and executed like I had never experienced before. That was incredibly exciting.

My boss—my immediate officer in charge—was a reserve officer. He actually wrote my Bronze Star. I had not worked for a reserve officer before, and he came in and he was leading us in maintenance. My three expediters came from different bases; it was really fascinating to be able to see that. But again, a testament to the consistency we saw across our Air Force in the preparation of readiness and then the mindset that our Airmen had about mission accomplishment.

That’s interesting. I know when you came back you went back to your base and you deployed again to Bahrain, and then you deployed again, I think, to Kuwait...

To Kuwait and then Bahrain, yes.

And this all happened before 9/11; so, I think, from an Airman who serves today, we tend to think of 9/11 as being a turning point where now we’re being deployed all the time. And in reality, you know, we did that quite a bit before then.

That’s right, yes.

What was the mindset of Airmen who served during the 1990s and were deploying regularly?

I think after Desert Shield/Desert Storm and the realization and fact that the Middle East was going to be an area that was going to be unstable, the focus was that we’ve got to be an expeditionary force.

You have to remember, too, we drew the force down as was preceded in history after many major conflicts. Going into Desert Shield/Desert Storm, we had nearly 600,000 active duty Airmen. We were close to probably a million strong if you took all the Total Force. From an active duty Airman’s standpoint, we drew that 600,000 down to nearly half that. The Guard and Reserve weren’t drawn down quite as much, but all drew down.

And now we’re half our size, yet our deployments are picking up. We’re having to deploy large numbers of Airmen and bed them down; so, we’re finding an imbalance. How do we set a tempo that gives us predictability and readiness? How can wings carry out our training objectives we need to have from a readiness standpoint?

A lot of that time period was trying to perfect the AEF or the Air Expeditionary Force structure, pre-identifying units and giving them a posture of when they would go. That’s how my deployment to Bahrain came from Moody Air Force Base. The 347th [Rescue] Wing, along with 4th [Fighter] Wing out of Seymour Johnson [AFB, North Carolina], the Gunslingers [366th Fighter Wing] out of Mountain Home [AFB], Idaho, and the 1st Fighter Wing at Langley Air Force Base, [Virginia,] were the four lead AEF wings for the fighter forces. Then your mobility forces organized in a little bit different way.

We started learning how to organize, train, and equip and be ready to put those together. That occurred during the time between 1990 and 2001. How do we set the right tempo and the right balance? How do we organize, train, and equip and be able to execute a mission, because the requirements did not go away? If anything, they were increasing over that period of time, and we were learning along the way to be able to adapt through that.

You mentioned the deployment requirements increasing, and with that, so do the sacrifices when it comes to time with family.

Absolutely.

How did the Airmen respond when it came to their motivation and their commitment to serve?

I think for the most part, for the Airmen that were continuing to serve, when they looked at those deployment time periods, they had a focus on mission that gave them a great sense of pride, accomplishment, and motivation. The flip side of that, as you talked about, is the sacrifice of the family left behind.

Then some of the imbalances of deployment after deployment started taking their toll. You take what was going on in American society—it was a great time in our nation. Unemployment was very low; the economy was steaming very well. So, what we saw in the late ’90s—I think 1999—is that we missed our recruiting goals for the first time in our history, and our retention was at the lowest we had had. So, now we are fighting the fact that not only are we having trouble retaining Airmen, we’re having trouble even recruiting Airmen.

Recruiters were having to use waivers to go out and get the force. We had a big initiative there to change and push up reenlistment bonuses. We also looked at, what do we have to do to balance things with the family? And again, that AEF process was all part of that, to try to give our Airmen more predictability so we would not have as many decide the sacrifices of service were too great.

We started putting a lot of emphasis then on family: family care, family readiness, the balance in our people’s lives. Because, as the facts presented themselves, we weren’t keeping the human resources that we needed, and we were having problems being able to bring them in.

You became the Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force in 2002, right after 9/11—right as Operation Enduring Freedom began and right before Operation Iraqi Freedom. That is when we saw the transition from the 1990s, where we were building up this expeditionary construct to a full bore expeditionary force. What were some of the primary challenges you saw when you took the seat?

I think for me, and from the very beginning of that timeframe, there was a question about the readiness of our force and the readiness of our enlisted force. Were they as ready as they needed to be?

One of the things that became apparent very fast, as we were going into Iraq and Afghanistan, is that Airmen had not experienced the closeness into the battlefield area—into where the conflict was. Conflict was totally different in this than at any time we had ever experienced, because it was not major force in a state-on-state. We’re in an area of strife, and many of our Airmen are starting to be outside the wire, exposed to things that I had never been exposed to. Desert Shield/Desert Storm was nothing like deploying into Operation Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom.

So, immediately it became, “Are we preparing our Airmen the way we should be?” That took me all the way back to my experience when I came in the Air Force at basic training. Basic training had basically changed very little from 1977 to 2002. There were some tweaks—Chief [CMSAF #12 Eric W.] Benken introduced Warrior Week. There was a determination that Airmen would become an Airman after the completion of Warrior Week, but it was still a six-week course. I touched an M16 two days in my entire six weeks of basic training. Airmen were still touching an M16 [rifle] two days in basic training and didn’t touch another one for a year, perhaps until they did their qualification training. So, my thought was that basic training needed to change.

One of the immediate changes we did is begin what I termed the BEAST: Basic Expeditionary Airman Skills Training. Inside of that six-and-a-half weeks, we deployed them into a deployed location and gave them threats of infiltration, mortar attacks, and things of that nature to a little bit more expose them to what an encampment would be at a base like Bagram [AB, Afghanistan], or other locations.

The other was to introduce them to rifles—we were able to bring in training rifles. I wanted to put real rifles in there, and I was told, “No, we can’t do that, we’d have to arm the Tis [training instructors].” And I said, “God no, we don’t want to do that. They’ll shoot somebody.” So, we gave them training rifles to use to give them more experiences along the way.

Of course, as we know today, I was able to gain, during my time, the funding to expand basic training to eight-and-a-half weeks versus the six weeks that we had. But, again, it was the focus on readiness. Are we focusing training correctly? For the first time, we had the in-lieu-of positions to support the Army. The Army was having a hard time being able to have the forces they needed; so, we started deploying convoy operations out of our transportation units. Our units were not set up as convoy operations; we had to learn that. We had to adapt to the type of training. We had to start sending Airmen to Army units to gain training. So, now we’re blending together a force different than we had in the past. A lot of that was on the fly. That became a great part of the focus I put on the enlisted force, making sure we looked at how we measured the readiness, and prepared Airmen for a lot of duties and tasks they had not been exposed to before.

What did you notice about how the Airmen responded to those changes?

I tell you, the resiliency of our Airmen, the adaptability, we use that phrase, “Flexibility is the key to airpower.” I was amazed at just how flexible, how adaptive our Airmen were.

and I visited units in Iraq and Afghanistan is that our Airmen had taken the Army system and how they approached convoy operations and adapted it through intelligence, communication, and all that they had as Airmen. They applied their Airmen skills, Airmen mindset to it, and we had lower casualty rates and better convoy operations set up in the Air Force. Even the Army came to recognize that the Air Force was adapting and making changes in convoy operations and were better than they were, and it had been one of their primary skills.

We were not organized, trained, and equipped that way; yet, we adapted. Then our transporters came back, and we took the most-recent experienced Airmen and put them with a cadre of instructors out at Camp Bullis in [San Antonio,] Texas. We were actually then taking real lessons learned right in the operation area and bringing that back to train the next group that was going to go over. It just amazed me again to see the adaptability of our Airmen, the intelligence and the ingenuity they had to be able to do that.

The other big changes that came with the push to be more expeditionary and more ready for the fight was the fitness program. You saw up close the transition to what we have today. Why was it important to make that move from the bike test?

Well, you know, I give that to General Jumper. It was the first task I was given by the boss—actually, before I even arrived in Washington. I had dinner with him one evening, and he turned to me and said, “Chief, the first thing I want you to do...,” and of course now I’ve got the Chief of Staff of the Air Force (CSAF), my new boss, telling me my first task. And he says, “I want you to work with me real close to help bring in a new fitness program in the Air Force.” And I’m like, “Really?” (laughter)

The vision he had for it, and just how committed he was, as we were preparing for Iraq and Afghanistan, to physical fitness as part of our total health—the physical, mental, spiritual well-being. He recognized the force was not as fit as he wanted it to be.

So, ultimately throughout all of the other things in my first year, I spent time working with primarily an officer from personnel and from medical, and we hammered out the new physical fitness program that we put in place.

The other thing I looked at was understanding what it was to change. I always looked at General Jumper as being one of the greatest change agents, of understanding that part of a change is not just telling people that you’re going to go do this. Part of change is recognizing how you get them to accept it, and knowing that it’s a cultural change. Culture change takes a period of time. Experts would tell you that a commitment to a major change in culture in an organization takes 7–10 years. We knew we weren’t going to be in the job 7–10 years; so, how did we put in place something that those behind us would continue to follow?

We also knew from the very beginning that no matter how much thought and preparation we put into it, we probably weren’t going to get it exactly right. Especially since we were using some different approaches to measurement–-again, how do you measure physical fitness? With all of us with different shapes and sizes of bodies, and males and females, how do you bring those standards about? We settled on the fact that there would be running involved, there would be push-ups and the sit-ups that were going to be the strength pieces of that—sit-ups for the core, push-ups for the muscular part of it.

Then there was the waist measurement. A little bit of controversy there, but we used good science. We went out to colleges and universities, doctors in medicine and physiology. We brought all of these things in to help us. It was not just something that was a whim or “Yeah, I think I like that.” We used science as part of it as well.

But I tell you, I think it was one of the greatest things we ever did. I go back to my time in the Air Force, the physical fitness aspect was go run a mile and a half once a year, and a lot of times that was pencil whipped, especially in my field. You get out there; if you can walk it, okay, you completed it type thing. This actually brought about a very serious focus on fitness.

The funding that we put in fitness centers—I had the opportunity to cut ribbons on brand new fitness centers across the Air Force. The uniform, I mean, when I deployed into Kuwait and Bahrain, we looked like a rainbow outfit. If we went out for physical fitness, we had every color shorts and pants. Then I go over and I look at my Army and Marine brethren, and they are out there in their fitness uniforms in formation—a team effort, together. So, I went into the Boss and said, “Boss, we need a fitness uniform to go with this as well,” and he agreed. He funded that right out of his pocket. We didn’t even POM [Program Objective Memorandum] it; we just did it.6 That was the other thing there—we were about changing the mind-set, changing the culture of our Airmen, and I would tell you today we are much better for it.

Yeah, and you mentioned the culture change and the time it takes. The fitness centers you look at today and just the way everyone approaches fitness—every morning the fitness center is full, every evening it’s full. You see teams running around base, and I think combine that with the approach in basic training and the expeditionary mind-set. Would you say Airmen are better today?

I would tell you that Airmen today are better trained, better equipped—and I mean equipped from the standpoint that they’ve got the tools. Are they flying the oldest airplanes in the history of our Air Force? Yes, they are. I mean the fact they we’re still flying B-52s and KC-135s and F-16s that are 25–30 years old...

I think though, from an Airman’s perspective today, the training and education is by far the highest we have ever seen in the force. Our education, our training, the readiness of the Force, and the experiences through deployments—the Airmen today, and especially the NCOs and our commissioned officers, if they are over three to four years in service, they have more deployment time, on average, than any of the force that went before them.

I don’t take anything away from the Airmen of the past, in any way. Those that preceded us back in the Army Air Corps, that helped birth us, at any given time in our nation, the commitment of the American spirit and our determination and will has been there. But I am so impressed with the Airmen today. How they have maintained where they are. A lot of that comes with the combination of education, knowledge, experience, and training they have.

Considering everything that you did during your tenure and the changes that we’ve mentioned, what made you proudest of the Airmen that served under you?

The team effort. When I was Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force, I told my immediate staff, “Look, when it comes to us, it’s not about me. It’s not about me as Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force; it’s about us as the Office of the Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force.”

When I led the unit at Moody Air Force Base, taking lessons learned from the past of the great unit at Myrtle Beach in the A-10 community...to go back and reset, to take those lessons learned...of course in maintenance, it’s all about processes, measurements, and metrics, using lagging and leading indicators, but the other part of that was establishing within the unit the team effort that it takes—and then a balance of family.

Of course, I take the lead from my wife. Sherry and I have been married the entire time. We were married before I came in the Air Force. We’re still married, and she is one of my great motivators. But to recognize and see the sacrifices that she had to make and that we made as a family through my deployments, gave me that sense that the family has to be a part of the unit as well. That’s the thing I try to impress upon people today. You can’t separate it.

Then remember, too, that we have a mission. You know, you gotta get ’er done. There is an objective out here that we’ve got to make, and that’s where the focus is: delivering the results. What we are here to do is to deliver airpower. So, those are the things I learned early and I tried to work on throughout my career.

That’s interesting. You mentioned your time at Moody, and I actually found that pretty interesting looking back over your career. One of the highlights is you heading to Moody and basically building up a unit and then leading it to break a ton of records. What was the secret to your success there?

Well, that’s that lessons learned. Myrtle Beach, you know, the leadership that I had at Myrtle Beach, the organization, everything put together. One of the great disappointments is that we closed Myrtle Beach. We drew the force down, and we set so many imbalances in the force. Stripping a force, cutting an active-duty force in half and doing that over the course of about a three-year period of time—we cut tremendous capabilities. We just riddled organizations in the force with the imbalances.

When I went into Moody, the first manpower document they gave me to set up the new unit, I was going to be 300-percent manned in master sergeants. I said, “I can’t have that many.” So, I went to work even before I got there, knowing I was going to be short five levels and seven levels except for the masters. No way I was going to take master sergeants and make them have to carry toolboxes. That was not what the master sergeants wanted to do. They wanted to be in charge of the flight, and yet now, look, I got to put you crewing an airplane. You’ve got the skills, you’ve developed that out there, that’s what you’re going to have to do, but, I was able to make those adjustments.

The other thing was that we were handed a big bill. As we moved to stand up that unit, they were already taking A-10s back into Kuwait. We knew we were going to be tasked to deploy immediately after IOC [initial operating capability]. So, we were the fastest since World War II. We declared initial operation capability in 90 days and then deployed the unit for 90 days after that. Then to bring it back after a deployment—that was all 24 aircraft by the way. We took every one of our aircraft, primarily the entire squadron. All of these people PCSed [permanent change of station] in, bedded down, established homes. You can imagine they have to get their families settled, get their kids in school, get settled down. Ninety days later we picked up and we deployed. Then it was to come home from that, and now let’s put this unit together. Now, what we are going to do is build the greatest unit.

Of course my mind-set, and some will tell you I was a tough chief, but my mind-set is that any unit that I am going to be in, if it’s not the best, then we’re going to make it the best. And now I am the chief, and I had officers that supported that. We’re going to be the best A-10 unit in the entire Air Force. We set an expectation that we are going to go do that, and we achieved the highest mission-capable rate of all the A-10s in the Air Force.

That’s cool. Good story. So, just one final question here for you, Chief. One of the things we’ve been asking the Chiefs is, when you take a look at the Air Force today, the Airmen who are serving, and you had to start a sentence with “I believe”—what would you say?

I believe our Airmen today are the best Airmen in the world. I believe our Airmen today have the best knowledge, training, and experience our Air Force has ever seen. I believe our Airmen will continue in every way they can to ensure our Air Force is, and will be forever, the greatest Air Force in the world.